The results showed that the Harris campaign, and Democrats more broadly, had failed to find an effective message against Mr. Trump and his down-ballot allies or to address voters’ unhappiness about the direction of the nation under Mr. Biden. The issues the party chose to emphasize — abortion rights and the protection of democracy — did not resonate as much as the economy and immigration, which Americans often highlighted as among their most pressing concerns. — The New York Times

Last week’s childrens’ story, written with the assistance of an A.I. language model, began with this prompt:

In the style of Grimm's Fairy Tales, tell the story of a Mayan oracle living in the Classic Era who tells the great Lord that a massive drought is approaching, and many will die unless they relocate the city-state 500 miles away to a completely different ecosystem. He knows this by reading the phenological signs and matching them to the Mayan almanac for the drought and wetness cycles. It has happened before, and entire city-states have perished. The Lord agrees this time and moves the city, conquering a large lake area and setting up his new capital on an island in the middle of the lake, so that there will always be plenty of water. Come up with a surprise plot twist and ending to the story.

For the past year, we’ve been exploring the theme of artificial intelligence, viral social media memes, how algorithms have been optimized for limbic activation (outrage, anger, fear), and how a few fortunate billionaires—largely selected at random rather than for some special fitness for purpose—have been directing this progression into our collective future unaware of the enormously destructive forces now unleashed.

In prior years I described the Maya Theatre State as a terminal phase of a vast, long-lived, and influential civilization, but one that was deeply flawed in its centralization of power, wealth inequality, brutality, and failure to understand non-negotiable eco-biophysical underpinnings. The parallel to the Maya Theater State of 800 AD and the Reality TV State of 2024 is stark. But let’s begin with a look at the Mesoamerican migrant tale that the AI model produced.

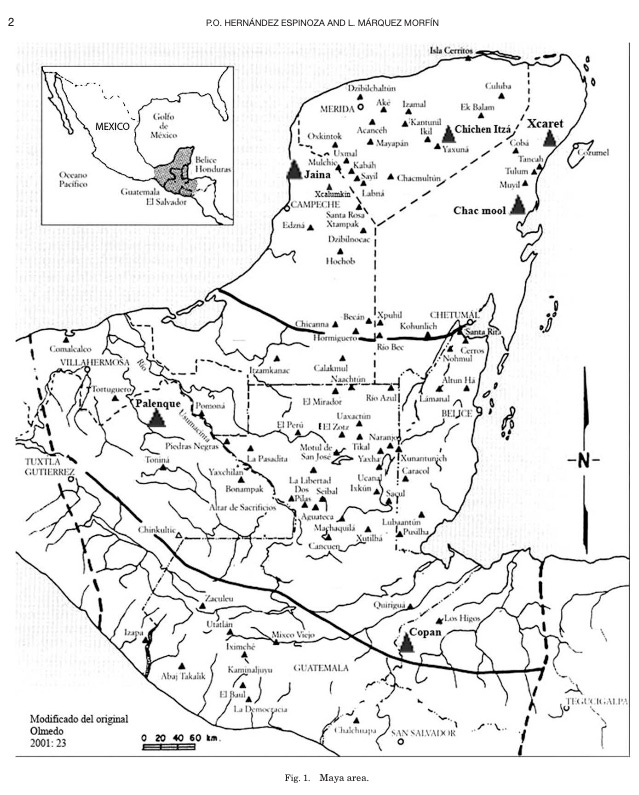

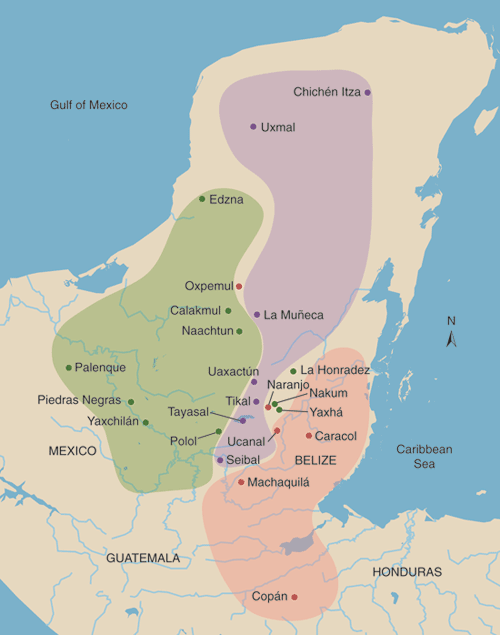

While last week’s story resembles the great Itzá Maya migrations, there were significant differences. Tikal, in southern lowland Guatemala, was one of the earliest and most prominent Itzá Maya capitals, dating to 300 BCE. For reference, Tikal was founded in the same era as Alexander the Great captured Gaza, genociding all its residents, and reorganized it as a center of Hellenic learning and philosophy on the Via Maris between Greece and Egypt. Tikal also coincides with the end of the Zhou dynasty—the time of Confucious—and the beginning of the Han dynasty that invented paper, water clocks, sundials, the seismograph, and a calendar of moon cycles.

In 378 CE, there was trade between Aztec capital Teotihuacan and Maya capital Tikal, which led to cultural and political exchanges. Then came the catastrophic climate change ending the Maya Classic period around 700 CE. The inhabitants of Tikal, the Itzá Maya, abandoned their city and migrated north to found Chichen Itza.

Uxmal, a significant site in the Puuc region of the Yucatán, is renowned for its architectural achievements and intricate stone carvings, but it was not built by the Itzá. Its proximity to Chichen Itza likely created linguistic, cultural, and trade ties and some cross-fertilization of the population.

Uxmal and Chichen Itza flourished during the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic periods (roughly 800-1200 CE) until the inhabitants of Northern Yucatán were once more beset by decades of drought and wildfire. Again, the Itza were uprooted, abandoning a monumental pyramid city to the jungle.

The Itzá relocated back to lowland Guatemala, settling on a drought-proof island in Lake Petén Itzá, where they built the new capital city of Nojpetén. When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the late 17th century, they renamed this shining city in the lake “Flores” (“flowers’).

Parallels to Modernity

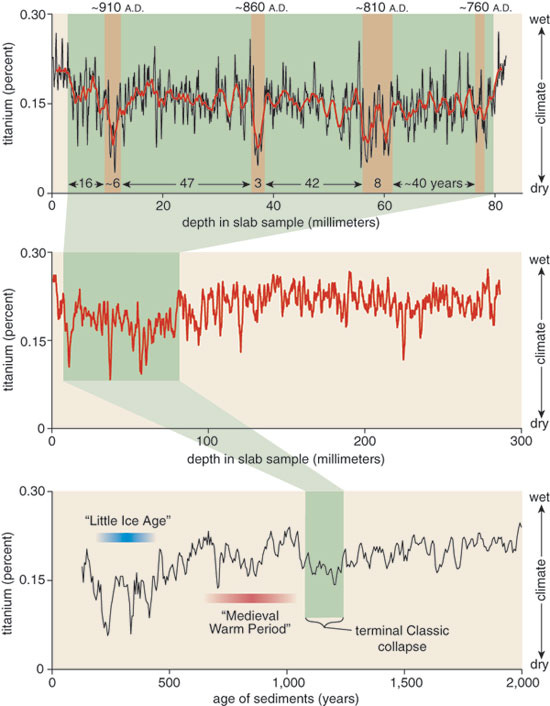

Migrating an entire population is not a minor undertaking, but to appreciate the full context, it is helpful to understand how much climate played a role in the development and decline of the Maya civilization. The Late Classic period (600–800 AD.) was characterized by territorial expansion, social complexity, and higher population density. Human density across the entire region was about 150–200/km2, or about like Sussex, New Jersey, or Devonshire, England today. In more urbanized areas, density ranged between 500 and 800 people/km2, similar to Gloucester County NJ, South Yorkshire, or Surrey. Density led to health deterioration, mainly from water and food contamination and vector-borne disease. The same effect is thought to be the cause of demise for Cahokia, North America’s largest (~200,000) city before the Columbian Encounter. Rural dwellers typically lived a third longer than their urban counterparts. In cities, only one child in five survived to reproduce. During the Terminal Classic period (790–889 AD), Tikal collapsed from adverse weather conditions and social-political pressures such as slavery and extreme income inequality.

Doubtless the migrating Itzá, said to be very war-like, were not hesitant to displace existing settlements when they relocated whole cities. In the climate disruption now unfolding, migrating civilizations may find a more challenging time uprooting established municipalities, but that doesn’t mean they won’t try and sometimes succeed.

Compared to the climate shifts in Mesoamerica in the First Millennium, orders of magnitude greater and faster shifts are coming in just the first century of the Second Millennium. The Maya had advanced knowledge of astronomy and used it to create complex calendars that correlated celestial events with the changing climate. They maintained extensive phenological observations and could tell what coming seasons might be like from patterns observed in centuries past. Long before satellites, they had excellent computer modeling.

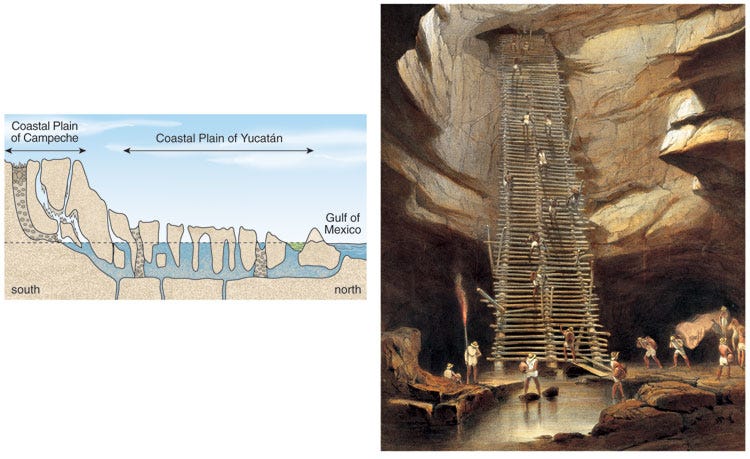

Given the importance of water resources in the karst terrain of the Yucatán, they also monitored cenotes (water-filled sinkholes) and other sources. They learned to farm on lakes (chinampas) and rely on the less variable productivity of animal-integrated long-rotation agroforestry (milpa). Milpa farming is closely tied to the zenith passage of the Sun, which occurs twice a year in the tropical latitudes of the Maya landscape. These passages were critical for predicting agricultural success or failure. The 260-day ceremonial calendar, which was part of the almanac system, was connected to both the agricultural calendar and the time it takes for corn to mature. This integration allowed for precise predictions of planting and harvesting times.

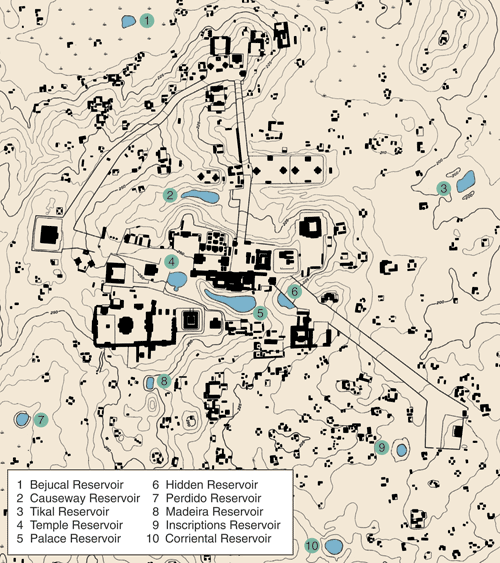

Amazingly, their mass migrations improved the Maya's capacity to produce food. The Yucatán Peninsula experiences drastically different annual precipitation among its regions, with as little as 500 millimeters in the North to as high as 4,000 millimeters in parts of the South. Dry, lowland cities like Tikal and Chichen Itza developed extensive water management systems, including large reservoirs and irrigation networks, which helped them better cope with drought periods, while wet, highland settlements managed extreme rains with frequent channels and above- and below-ground water features. They developed elaborate terrace and irrigation systems to protect against soil runoff and nutrient depletion, and they optimized for use efficiency and storage.

These are lessons we should be relearning as our climate shifts, migrations swell, and food production becomes more and more challenging.

The AI bot concluded:

These adaptations show that the Maya were not passive victims of climate change but actively responded to environmental challenges, although their strategies were only effective up to a point. The Maya's experience highlights the importance of taking a long-term perspective in adapting to climate change.

To this, I would add that the greatest population reached by the Mayan civilization during its peak is estimated to have been between 7 to 11 million people (and 6 to 7 million people still identify as Maya ethnicity and speak a Mayan language as their first language today). By 2050, at least 1.2 billion people will be displaced due to climate change and natural disasters, with regions like Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America most rapidly abandoned. What we see in places like Chimney Rock and Valencia in the 2020s is merely a prelude—an omen, or foreshadowing. Migrants out of Central America and Mexico alone will reach 1.5 million annually just in the next 2 decades. By 2070, Sahara-like conditions will cover a significant portion of the Earth’s land surface, affecting billions. The Itzá Maya never had it quite that bad, but they did not have our tools to assess the hazards and react, either. Whether our high lords will choose to listen to what their science shamans are telling them and react in time remains the greatest mystery.

Ruddiman, Dull, Nevle and others have argued that the re-growth of neotropical forests following the Columbian encounter led to terrestrial biospheric carbon sequestration on the order of 2 to 5 GtC, contributing to the well-documented decrease in atmospheric C recorded in Antarctic ice cores from about 1500 through 1750 CE. When European disease and slavery swept the Americas so much forest was released — much of it with millennial build-ups of latent soil fertility — that atmospheric CO2 plummeted and Europe literally froze. The Swedes invaded Denmark over frozen ocean, Louis XIV put parquet floors into the palace at Versailles, and Hans Brinker won his silver skates on the Dutch canals.

Dr. Dull gives us hard numbers for what Charles Mann has tried to get across to us in 1491, that we don’t give mankind nearly enough credit for creating our biosphere. Just as Michael Pollan’s Botany of Desire showed us how plants have manipulated us to spread them around the globe, the message of man’s mutuality with nature is more than seeping into the data everywhere.

— Erich J. Knight (1955–2018)

From charcoal in lake bed studies we can see that increased biomass burning and deforestation during agricultural and population expansion in the Yucatán from 2500 years ago corresponded with atmospheric carbon loading and global warming 1100 to 650 years ago. The Maya changed the weather, just as did the Egyptians, Ottomans, Mongols, Apaches and Nigerians. During the rise of the Classic Maya, the Great White Cities witnessed by Orellana in the first European transit of the continent, the vast palisade cities along the Mississippi encountered by DeSoto, and at trade centers like Cahokia and Teotihuacan, so much carbon was released from forest and field that the atmosphere loaded and the northern hemisphere warmed. At the same time, there was desertification in North Africa, driving the Moors into Spain. Humans and climate are inextricably connected. They always have been. Westerners just didn’t grok that.

Life created the conditions for life. Forest farming moderated Ice Ages. Whaling wrecked Earth’s largest carbon sink. Genghis Khan’s Golden Hoard cooled the planet. Urbanization of the Levant in the 20th Century warmed it. Quantum entanglement is everywhere, all at once.

References:

Camacho-Villa, T.C., et al. 2021. ”Mayan traditional knowledge on weather forecasting: who contributes to whom in coping with climate change?" Frontiers in sustainable food systems 5: 618453.

Douglas, P.M., et al., 2015. Drought, agricultural adaptation, and sociopolitical collapse in the Maya Lowlands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(18), pp.5607-5612.

Dull, Robert A. , Nevle, Richard J. , Woods, William I. , Bird, Dennis K. , Avnery, Shiri and Denevan, William M. ‘The Columbian Encounter and the Little Ice Age: Abrupt Land Use Change, Fire, and Greenhouse Forcing’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 01 September 2010.

Epstein, R. et al., 2024. Devastated Democrats Play the Blame Game, and Stare at a Dark Future, The New York Times, Nov 14, 2024, page 1.

Ford, Anabel, and Ronald Nigh. “Climate change in the ancient Maya forest: resilience and adaptive management across millennia.” The Great Maya Droughts in Cultural Context: Case Studies in Resilience and Vulnerability (2014): 87–106.

Hall CAS, McWhirter T. 2023 Maximum power in evolution, ecology and economics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 381: 20220290.

Hernández Espinoza, Patricia Olga, and Lourdes Marquez Morfin 2015. ”Maya paleodemographics: What do we know?." American Journal of Human Biology 27.6: 747-757.

Iannone, G. ed., 2014. The great Maya droughts in cultural context: case studies in resilience and vulnerability. University Press of Colorado.

Kennett, Douglas J., et al. 2022. ”Drought-induced civil conflict among the ancient Maya." Nature communications 13.1: 3911.

Meierhoff, J. 2022. "Nineteenth-Century Maya Refugees at Tikal, Guatemala." Coloniality in the Maya Lowlands: Archaeological Perspectives 171.

Oh, N. 2013. ”Climate Change and the Decline of Mayan Civilization." Conflict and Decay 2: 24-25.

Peterson, L. and G. Haug, 2003. Climate and the Collapse of Maya Civilization American Scientist

r/dataisbeautiful 2024. Population density of each county in England.

Shelton, J. 2015. Finding signs of climate change and adaptation in the ancient Maya lowlands, Yale News.

Whitmore, Thomas J., Mark Brenner, Jason H. Curtis, Bruce H. Dahlin, and Barbara W. Leyden. 1996. “Holocene Climatic and Human Influences on Lakes of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico: An Interdisciplinary, Palaeolimnological Approach.” Holocene 6 (3): 273–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/095968369600600303.

Willey, Gordon R. 1974. “The Classic Maya Hiatus: A Rehearsal for the Collapse?” In Mesoamerican Archaeology: New Approaches, edited by N. Hammond, 417–30. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Meanwhile, let’s end these wars. We support peace in the West Bank and Gaza and the efforts to bring an immediate cessation to the war. Global Village Institute’s Peace Thru Permaculture initiative has sponsored the Green Kibbutz network in Israel and the Marda Permaculture Farm in the West Bank for over 30 years and will continue to do so, with your assistance. We aid Ukrainian families seeking refuge in ecovillages and permaculture farms along the Green Road and work to heal collective trauma everywhere through the Pocket Project. You can read all about it on the Global Village Institute website (GVIx.org). Thank you for your support.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger, Substack and Medium subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions can be made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration.

當人類被關在籠内,地球持續美好,所以,給我們的教訓是:

人類毫不重要,空氣,土壤,天空和流水没有你們依然美好。

所以當你們走出籠子的時候,請記得你們是地球的客人,不是主人。

When humans are locked in a cage, the earth continues to be beautiful. Therefore, the lesson for us is: Human beings are not important. The air, soil, sky and water are still beautiful without you. So, when you step out of the cage, please remember that you are guests of the Earth, not its hosts.

We have a complete solution. We can restore whales to the ocean and bison to the plains. We can recover all the great old-growth forests. We possess the knowledge and tools to rebuild savannah and wetland ecosystems. It is not too late. All of these great works are recoverable. We can have a human population sized to harmonize, not destabilize. We can have an atmosphere that heats and cools just the right amount, is easy on our lungs and sweet to our nostrils with the scent of ten thousand flowers. All of that beckons. All of that is within reach.