Dogs and money share a common Latin etymology. The word “pecuniary,” which means an economic interest, from the Latin pecus (trade), comes from the proto-IndoEuropean péḱu (livestock). It makes sense because animals were commonly exchanged in the barter world that pre-existed coins. As proto-IndoEuropean evolved into proto-Italic, péḱu spun off ḱwṓ and then kō (dog). When the Romans arrived, dogs became canes and then canis. The word was also used to connote someone of low birth or foul smell. Roman coins became the standard of pecunia (trade). The Latin name for dogs today, Canis lupus familiaris, recalls the descent from wolves (lupus) into domestication (familiaris).

At least in the Western world, dogs and money have never been far apart. Rather than considering pet ownership in relatively wealthy nations like the US, UK, Japan, or parts of the EU, let’s look at the example of a less wealthy nation like México. According to the Mexican Association for Food Production, about a million tons of food are produced in México for dogs every year, but even that is insufficient to meet demand, and the remainder is imported. Dogfood is a $40 billion peso ($2 to 3 billion dollar) industry but only about 30% of Mexican dogs have homes. Anything eaten by the other 70% is off the books.

México has no census of pets, but the Enbiare, which measures a person’s view of well-being in different dimensions of their social life, says that around 25 million Mexican households are home to an estimated 43.8 million dogs. Assuming feral dogs represent 70% of the total dog population, the entire number, from Chihuahuas to St. Bernards, would be 146 million.

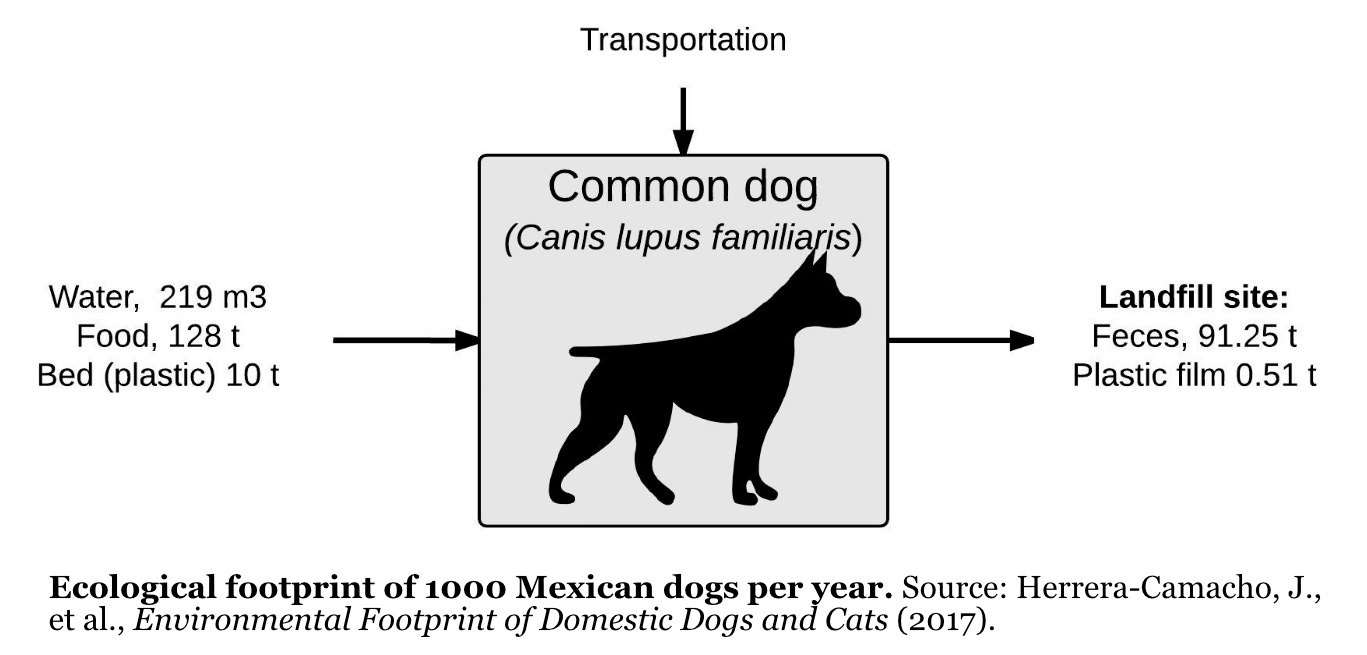

In México it is estimated that each dog’s environmental pawprint is 0.85 ha./y just for their food (Ravilious, 2009). Multiply that number by 146 million dogs, and the country needs to devote 563,709 square miles (124 million ha.) to providing for its dogs. México’s total land area is 758,449 square miles.

The ecological footprint is a popular natural resource accounting tool that is used to measure environmental sustainability. Specifically, it is the total area of productive land and water required to continuously produce all resources consumed and to assimilate all waste produced by a defined population wherever on Earth that land is located (Wackernagel and Rees 1998, Csutora et al. 2009).

—Martens, Su and Deblomme (2019)

Mexico’s dogs have a larger ecological pawprint than the territorial area of 183 different countries. It’s larger than France, Spain, Iraq, Congo, Sweden, Finland and Norway. Cortes, who introduced the Spanish breeds to México, should be spinning in his grave.

La Cuenta, por Favor

Of course, México does not pay for that footprint or land use. Like everyone else, it puts it on a credit card and charges it to future generations. This means that future generations, should there be many, will have diminished biodiversity, farmland, forest, water, and habitable climate as the bill comes due. And the authors of the ecological footprint report warn that their study may understate the full impact.

… the ecological footprint of pet animals is only part of the problem, and the environmental impacts of abandoned animals on the streets could be bigger than those who have an owner.

You are far more likely to be attacked by a dog than by any other large animal (4 to 10 million per year just in the US). Dog bites are responsible for around 30,000 human deaths per year, compared worldwide to 6 for sharks and 22 for lions.

The survey, “Mexico, a pet-friendly country,” was carried out by Mitofsky, a Mexican research group, in 2019. Asked if they buy special food for their pets, 57.7% of pet owners answered yes; 8.9% said the dog eats the same food as the family, and 32.4% said it was some combination of the two.

Food is not the only financial bite for dog owners. Asked how often they take their pet to the veterinarian, 21.2% said once a year; 28.2% said twice a year; 16.3% said three times; 7.6% said four times; 7.1% said five times; 2.5% said six times; 5.5% said seven times and 11.6% said never.

México is not a wealthy country but it has a wealthy class of citizens. Class differences cannot explain 146 million dogs in a nation of 127 million people. It's just that México is, as the pollster said, “a pet-friendly country.”

But who is “pet-friendly” really friendly to? Certainly not the Earth or future generations. Likely not to the poorer classes struggling to make minimum wage. Minimum wages in México averaged 29.42 MXN/Day ($1.73) from 1960 until 2024. In January 2024 the federal standard was raised to $14.65/day (249 MXN), but dog food costs the same in México as it does north of the border.

Owning a dog is a modern form of indentured servitude, costing many Mexicans more than they would spend for a car, apartment, or college tuition. For most, the costs go unnoticed because dogs are part of the culture—you grew up with them and there is normalcy bias.

For at least the last 200 years, dogs and money, like dogs and fossil fuels have never been far apart. Nearly 100 million dog bites will be reported this year around the world. That number doesn’t include the bite to their owners’ or victims’ pecuniary security.

References

Herrera-Camacho, J., Baltierra-Trejo, E., Taboada-González, P. A., Gonzalez, L. F., & Márquez-Benavides, L. (2017). Environmental Footprint of Domestic Dogs and Cats.

Martens, Pim, Bingtao Su, and Samantha Deblomme. "The ecological paw print of companion dogs and cats." BioScience 69.6 (2019): 467-474.

Navarro, S. Pets in Mexico, a sector invisible to statistics, Yucatan Times, March 7, 2023

Pet-Food-Industry, 2016. Changing lifestyles are expected to aid pet food market growth, in: Secondary Pet-Food-Industry (Ed.), Secondary Changing lifestyles are expected to aid pet food market growth. Pet Food Industry, U.S.A.

Ravilious, K., 2009. How green is your pet? New Sci. 204, 46-47. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(09)62827-X.

Salemdeeb, R., zu Ermgassen, E. K. H. J., Kim, M. H., Balmford, A., Al-Tabbaa, A., 2017. Environmental and health impacts of using food waste as animal feed: a comparative analysis of food waste management options. J. Clean. Prod. 140, Part 2, 871-880. doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.049.

Meanwhile, let’s end these wars. We support peace in the West Bank and Gaza and the efforts by the Center for Constitutional Rights, National Lawyers Guild, Government of South Africa and others to bring an immediate cessation to the war. Global Village Institute has sponsored the Green Kibbutz network and the Marda Permaculture Farm in the West Bank for over 30 years and will continue to do so. We also aid Ukrainian children seeking refuge in ecovillages and permaculture farms along the Green Road. You can donate by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by sending donations to us at greenroad@thefarm.org. There is more information on the Global Village Institute website (GVIx.org). Thank you for your help.

All Patreon donations and Blogger, Medium, or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity.

My latest book, Retropopulationism: Clawing Back a Stable Planet from Eight Billion and Change, is now available. Complimentary copies should reach Power Up! Patreon donors soon.

If you are interested in climate solutions, one of the world’s most effective conferences will be in Sacramento February 12–15. Contact me directly for a $200 discount on registration. Some of the latest inventions will be in the exhibit hall.

Following that, I will be in Santa Barbara for the 2024 Eco Hero Award. Y’all are invited!

Thank you for reading The Great Change. This post is public so feel free to share.