Building a Chinampa

Five hundred years ago, the fortuitous combination of agroforestry and aquaculture was unbeatable.

This week I donned my tall boots and waded back into our constructed wetland to restore and rebuild the chinampas. Rob Wheeler, for more than 20 years the Global Ecovillage Network representative to the UN Headquarters in New York, brought along loppers, a machete, and a portable saber saw to assist me. During my nearly three years of pandemic absence, the wetlands had taken on a life of their own and become a swampy thicket of fallen branches, bent-over bamboo, and nettles. One could be forgiven for not seeing beneath all that to what it will eventually become—the most productive food system, on a calorie per square foot basis, ever devised by humans.

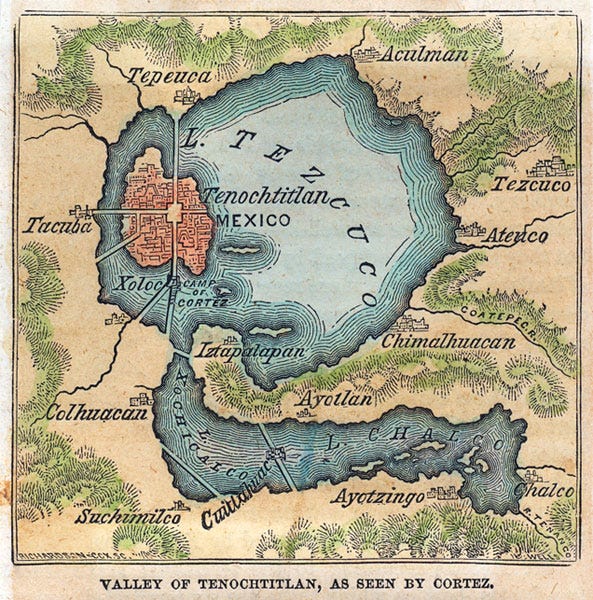

A chinampa is defined by the Encyclopedia Britannica as a “small, stationary, artificial island built on a freshwater lake for agricultural purposes.” The word was originally from the Nahuatl word chinamitl, “woven fence or hedge,” made from the native willow, Salix bonplandiana. At the time Hernán Cortés arrived at the Halls of Moctezuma, the word was synonymous with a southern region in the Valley of México centered on Xochimilco.

Traditional chinampas are biodiverse; they can be kept in almost continuous cultivation, their soils are renewable, and they create a microenvironment that protects crops….

—Roland Ebel, in Hort Technology

The Conquistadors could not fathom the island city of Tenochtitlan when, on November, 8, 1519, they crossed the Ixtapalapa causeway over Lake Texcoco and beheld the spectacle of its glimmering central pyramid, broad white boulevards, and flowered verges. It was the most beautiful city any of them had ever beheld. Cortés and his men marched across the causeway until they were met by the Aztec Emperor, Moctezuma II, who greeted them, descending his royal litter to offer gifts. Moctezuma was immediately taken prisoner and ransomed for gold and silver. Once the ransom was paid, he was executed.

Six months later the Aztecs rose up and threw out Cortés, but it was too late. While the Spanish army spent 1520 exiled to Tlaxcala, General Smallpox ravaged and decimated the city, reducing its mighty army to bleeding pustules. Cortés returned in 1521 and razed what remained. He wanted no one in Europe to see what he had seen, so he took down the pyramid and turned around the stones in walls and boulevards to rough sides out. He ordered construction of Catholic churches on the pyramid mounds. He burned the codices, executed the royal heirs, and attempted to erase all traces of the old order. Tenochtitlan was renamed “México." Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente Motolinia described the reconstruction:

The seventh plague was the construction of the great City of México, which, during the early years used more people than in the construction of Jerusalem. The crowds of laborers were so numerous that one could hardly move in the streets and causeways, although they are very wide. Many died from being crushed by beams, or falling from high places, or in tearing down old buildings for new ones.

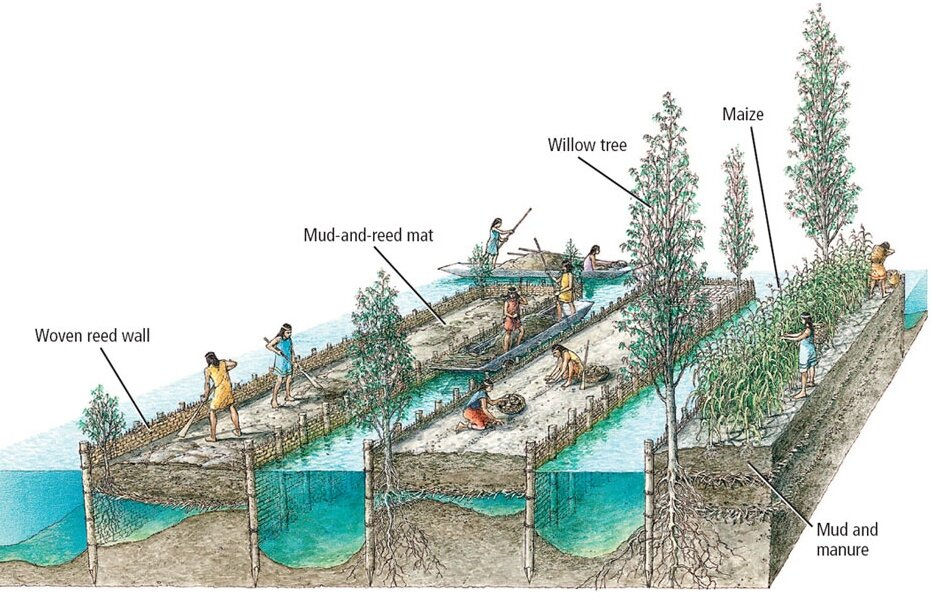

Among the engineering wonders deconstructed by the slave gangs were the vast systems of chinampas that were how a dense metropolitan population of more than 100,000 was sustained in the dry central valley of México. These earthworks consisted of alternating narrow islands and canals, initially formed by willow fences and composted fill from the kitchen wastes, lake mud, rubbish and sewage of the lakeside villages, planted with fruit and nut trees to line and hold the banks and gardens of corn, beans, and vegetables. Freshwater fish were trapped by fences in the canals where they ate mosquito larvae and grew fat on falling fruit until they could be netted and brought to market.

An Engineering Wonder

A 2014 study of the chinampas in the 70-square-mile Lake Chalco-Xochimilco found they were built between the mid-15th and early 16th centuries at the peak of the Aztec Triple Alliance. In a ten-square mile study area, 23,094 relic beds and 400 mounds were digitized for mapping. The long, narrow beds averaged 3.75 meters wide and had an average length of 49.4 meters, with a land-to-water ratio of 1.07:1. In addition, there were many small lakeside homes and villages, large wharves comprised of multiple mounds and platforms, open pools, and wide canals.

According to the researchers, chinampas allowed frost and flood protection, nutrient recovery, and irrigation by splash or scoop techniques from canoe-bound farmers during droughts (the standard tool was a lacrosse-stick-like ladle called a zoquimatl). Normal capillarity flows from the lake through the island eliminated the need for irrigation in normal dry cycles. Large amounts of algae (known as tecuitlatl) were collected from the surface of the Lake and used to make high-protein bread and cheese-type foods. This alga is still grown in México for fertilizer.

These village-wharves probably formed the economic and social hub for the lakeside tenant farmers who were comprised of free peasants (macehualtin), serfs (mayeque), and slaves (tlacotin). Aztec chinampas built through land reclamation existed outside the traditional corporate land holding capolli system and tenant farmers obtained rights of cultivation in return for approximately 50% of their agricultural production in rent payment to land grantees residing in Tenochtitlan.

After the consumption needs (dietary and non-dietary) of some 30,000 lakeside resident farmers, boatmen and fisher families were met, an annual 10,000-ton maize-equivalent agricultural surplus reached the storehouses and markets of Tlatelolco-Tenochtitlan and would have been enough to feed 50,000 persons for a year. Considering this study area was perhaps only ten percent of the full chinampas complex of the watershed, it is reasonable to project an annual surplus of 50- to 100,000 tons of high-calorie foods—roughly 2 to 4 shipments per year the size of the recent Odesa-to-Istanbul grain lift from Ukraine.

The fortuitous combination of agroforestry and aquaculture was unbeatable, but when the conquest killed off the engineers who maintained lake levels, the chinampas and low-lying cornfields sank below the marshy lake surface. Floods carrying human waste spread endemic diseases. The mosquito population grew and brought more diseases.

The Spanish Viceroy ordered drainage engineering in the style of the Old World. He infilled the lake, wiping out fish, birds and the lakeside villages that had grown the food for the city. And yet, the city flourished as a trade center based upon slavery and silver, such that when it was visited by Alexander Von Humboldt in 1803, it was called the “City of Palaces.”

By then, what is today’s largest city in North America had lost the ability to sustain its own population. It had lost its orchards, cornfields, lake fish, and the natural advantage of the indigenous wisdom that had created the miraculously productive chinampas.

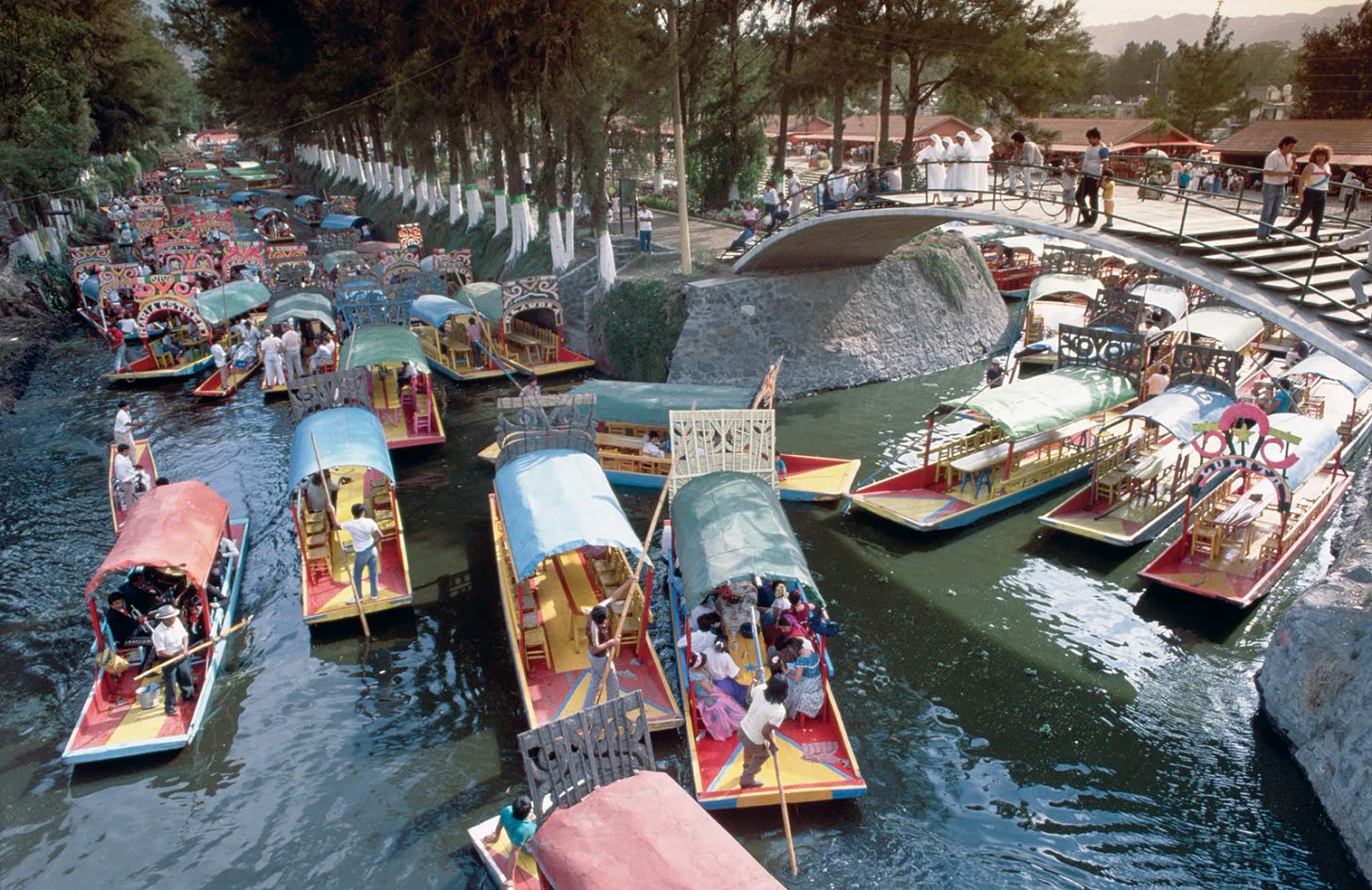

The islands were exposed for a short period in the mid-20th century after lake drainage was completed and before Green Revolution machinery obliterated the garden mounds. In the Xochimilco region, the chinampa area under cultivation decreased by more than 60 percent after World War II. Nevertheless, those that remain maintain their highly productive yields on relatively low inputs. Today they mainly grow flowers for the Zocalo market in Mexico City and take tourists on gondola rides. Most city planners assume that the Xochimilco water gardens will be entirely converted into gated residential communities (colonias) by 2057.

Today the loss of the chinampas has worsened forest degradation, erosion, floods, land sinking, pollution of soil and water, water retention and infiltration, and biodiversity. Farmers now must cope with increasing pest populations and the stench of fetid waters in the remaining lakes. Were México to seize the opportunity to restore the chinampas to provide food and water to its largest metropolis, chinampa soils would sequester large quantities of carbon.

However, due to their humidity and high organic matter, the greater microbial activity would also favor greenhouse gas emissions. A study performed in Xochimilco indicated that emissions of carbon dioxide were generally low, but that nitrous oxide and methane were high, and made worse by frequent irrigation. Of course, Mesoamerican peoples controlled for that by the addition of GHG-scavaging biochar.

It is unlikely carbon sequestration will tempt the current president, the son of an oilfield worker and a climate change denier, but beyond Mexico, regions that could benefit from broad-scale chinampas include the Mississippi River Delta, the Hudson River Delta, extensive parts of Florida, the Great Lakes Region in the United States and Canada, the Pantanal region (Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay), the eastern and western Congolese swamp forests, the African Great Lakes region, eastern South Africa, Shanghai and the Yellow River Delta in China, the Kutch District and parts of the state of Kerela in India, the Padma River Delta and (almost all) southern Bangladesh and neighboring India, the Yangon Metropolitan area in Myanmar, extensive parts of Sumatra (Indonesia), the Mindanao River in the Philippines, the Rhone River Delta in France, Hamburg in Germany, the Mersey Delta in England, the Gulf of Finland (Finland, Estonia, Russia), and the Darwin Area and Western District Lakes near Melbourne in Australia.

As Rob and I thinned the overgrown thickets of bamboo, we lay our cut canes and nettles atop the islands and reestablish the free-flowing canals through the 11,000 sq ft alternating lagoon and reed-bed system. We will need to build more topsoil before we can think about food crops on the islands, but for now, the water will again circulate around them, infiltrating new soils at the root zone, nourishing future plants in times of drought, and protecting the site from flooding in times of torrential rain. They will also form a wet barrier in the path of any forest fires moving upslope towards our buildings.

Turtles, hummingbirds, and dragonflies watch and marvel as we labor. This is a system of food production that is preparing itself for climate change.

In several reports to the King of Spain written in the year 1520, Cortés acknowledged the grandeur of the Aztec capital, “as large as Seville or Cordoba” but incorrectly gave the city’s name as Temixtitlan instead of Tenochtitlan. It is possible that once established in his palace in Coyacan he was served a chinampas meal fit for royalty—cornmeal crusted fish, candied pumpkin, sweet corn with nopal cactus, and the thin corn flatbread that the Aztec called tlaxcalli which the Spanish mispronounced “tortillas.” The recipe might have gone something like this:

Chinampas Fish Fillets with Calabaza En Tacha

Serves 2

Ingredients:

2 (6-ounce) tilapia fillets

1 nopal cactus

1 small (2 lb) pumpkin squash

1 c kerneled sweet corn

2 limes

1 tomato

1 small onion

1 chili pepper

⅓ c yellow cornmeal

1 Tbsp all-purpose flour

½ c masa harina, (not cornmeal)

1½ c water

1 c grated piloncillo, or brown sugar

1 tsp sea salt

1 tsp cinnamon

1 Tbsp cacao powder

2 Tbsp maguey agave syrup

¼ tsp dried oregano

¼ tsp dried yerba santa

¼ tsp freshly ground black pepper

8 small, handmade corn tortillas

Preparation

Calabaza En Tacha

Quarter pumpkin and remove seeds

Wash, drain and reserve the seeds

In a medium saucepan simmer 1 c water, 1/2 c piloncillo, and the juice of one lime until the piloncillo is dissolved

Add the pumpkin quarters and bring the mixture to a boil

Reduce the heat to low and simmer, covered, for a half-hour

Remove the lid and simmer for an additional half-hour, until the pumpkin is tender and the sauce reduced to a glaze

Remove squash and drain

Blend cacao powder, 1/2 tsp cinnamon and maguey agave syrup and garnish squash quarters

Sprinkle evenly with ¼ tsp salt and ¼ tsp pepper

Place quarters in a shallow pan in oven and bake for 20 minutes at 350°F

Âtōle Breading

In a medium saucepan combine masa harina, water, milk, piloncillo (or brown sugar), and 1/2 tsp cinnamon. Whisk the mixture and bring to a simmer over medium-high heat, whisking often.

Reduce the heat gradually for 5-10 minutes, whisking often, until your desired consistency is reached.

Remove the ātōle from the heat and combine ⅓ c yellow cornmeal.

Bread the fish fillets

Fried Fish

While the squash is simmering:

Scrape spines and hairs from nopal cactus

Julienne nopal, chili, onion and tomato

When the squash is baking:

Toast tortillas on hot comal, remove and keep them warm in linen

Toast squash seeds on comal

Blend vegetable ingredients with squash seeds and kernelled corn on comal at medium heat

Grind or pulverize oregano and yerba santa to fine flakes and sprinkle atop comal mixture

When corn mixture begins to brown, gently lay fillets on comal and raise the heat

After 2 minutes turn the fillets and smother them in roasted corn nopal mixture

Cook another 2 minutes or until fillets flake easily

Serve

Remove squash from oven and fish with corn-nopal covering from comal and plate

Quarter the lime and place two slices on each of the serving plates

Place warm tortillas in linen in basket at table

Serve with the beverage of your choice

Note: All of these ingredients would have been used by the residents of Tenochtitlan before 1520. Although oils of avocado, coconut and other plants would have been available to them, they did not use these for frying. They did not have iron skillets and instead used the comal.

Towns, villages and cities in the Ukraine are being bombed every day. As refugees pour out into the countryside, they must rest by day so they can travel by night. Ecovillages and permaculture farms have organized something like an underground railroad to shelter families fleeing the cities, either on a long-term basis or temporarily, as people wait for the best moments to cross the border to a safer place, or to return to their homes if that becomes possible. So far there are 62 sites in Ukraine and 265 around the region. They are calling their project “The Green Road.”

The Green Road also wants to address the ongoing food crisis at the local level by helping people grow their own food, and they are raising money to acquire farm machinery, seed, and to erect greenhouses. The opportunity, however, is larger than that. The majority of the migrants are children. This will be the first experience in ecovillage living for most. They will directly experience its wonders, skills, and safety. They may never want to go back. Those that do will carry the seeds within them of the better world they glimpsed through the eyes of a child.

Those wishing to make a tax-deductible gift can do so through Global Village Institute by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by directing donations to greenroad@thefarm.org.

There is more info on the Global Village Institute website at https://www.gvix.org/greenroad

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration #ReGeneration

“There are the good tipping points, the tipping points in public consciousness when it comes to addressing this crisis, and I think we are very close to that.”

— Climate Scientist Michael Mann, January 13, 2021.

Want to help make a difference while you shop in the Amazon app, at no extra cost to you? Simply follow the instructions below to select “Global Village Institute” as your charity and activate AmazonSmile in the app. They’ll donate a portion of your eligible purchases to us.

How it works:

1. Open the Amazon app on your phone

2. Select the main menu (=) & tap on “AmazonSmile” within Programs & Features

3. Select “Global Village Institute” as your charity

4. Follow the on-screen instructions to activate AmazonSmile in the mobile app

The Great Change is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.