Does Mother Nature have a plan to avert Terminal Climate Shock?

Not all tipping elements are bad.

After years of drought, last winter a mind-boggling 51 atmospheric rivers dumped rain and snow on California. Those rivers then shifted to Florida, causing multiple flooding events, the worst of which was earlier this month. The East and Northeast were not spared, with significant floods in December and January. Montpelier Vermont got eight inches (20.3 cm) in 24 hours. Then Texas and Louisiana experienced downpours that dropped a month’s rain in a day. After the rain broke records in Florida, New York City and Philadelphia, it slammed the mid-continent last week, sweeping away towns in Minnesota, Iowa and South Dakota. At this writing, the situation in Spencer and North Sioux City remains critical with more rain forecast.

The NOAA Climate Prediction Center predicts that up to 13 hurricanes could develop in the Atlantic Ocean this year, at least four of which could be major. For coastal and peninsular residents, that means more rain.

After watching Earth climate systems blow past so many threshold markers for tipping elements in 2023 and 2024, many scientists have been openly expressing worries about our chances of arresting it. Some hold out hope that a shift from the El Niño cycle to La Niña in 2025 (by no means guaranteed) will revert surface temperatures and provide a respite from extreme events. Others advocate for technofixes like all-out transition to renewables (Michael Mann, Katherine Hayhoe), nuclear power (James Hansen, Sabine Hossenfelder), or marine cloud brightening (Leon Simons, Paul Beckwith). In my view, none of those is more than a bandaid (or in the case of nuclear, a fresh wound) unless we are also willing to radically (meaning going to the root) switch the dominant paradigm to living leaner and redesigning our civilization to farm and build with carbon in all its myriad forms.

Petroleum executive Colin Campbell many years ago compared our current moment in geological history to arriving at the tavern after final call and being so thirsty you take out your pocket knife and cut up the carpet to squeeze out any last drops of spilled beer (and whatever else might be there). At the time he made that comparison fracking and gas wells had not yet gained the popularity they have today, but the analogy was nonetheless apt. Oil discoveries worldwide have not kept pace with extraction for many years. The situation is especially acute in post-peak producer nations like the USA, Venezuela and México. Fracking is scraping the bottom of those formations, and the more of it you do, the sooner the province runs dry. There is no point waiting for that moment. By the time we extract the last drops we will have ushered in our own extinction from climate change. We need to just stop now.

Where are the Tempering Feedbacks?

We know that nature has feedbacks that are both positive and negative. Some are like squirting lighter fluid on the barbecue. They are accelerants. Others are like riding a bicycle, you lean to the left or right, depending on which way equilibrium is out of balance, and your center of gravity keeps you upright.

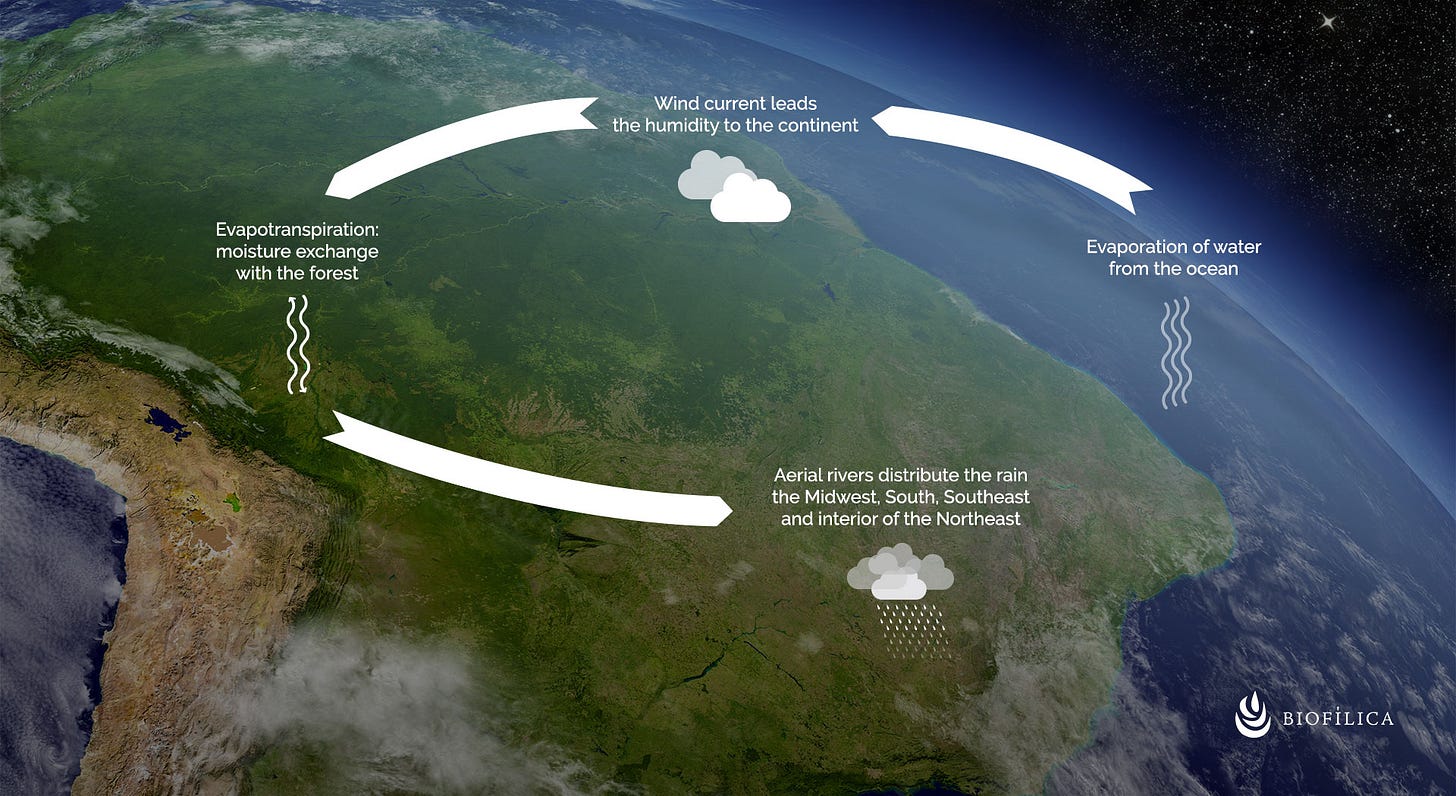

Take a rainforest. At some stage of its expansion, it grows so large that it creates its own weather systems. Not only does that make a favorable water cycle to support plant growth, even in otherwise inhospitable conditions, but it exports water vapor—clouds—to the air currents circling the globe in the lower, mid-range, and upper atmosphere. Those circulations are driven by the spin of the Earth, the pull of the Moon, and the heat of the Sun. That water vapor, seeded by dust nuclei, forms raindrops and spreads the surplus wealth of the rainforest, the product of its trees, to distant lands and to the ocean.

Another example is the topsoil of North Africa, or I should say, the sand. When it gets very hot and very dry, mineral particles are picked up and lofted high into the wind. They carry westward on the jet stream, some of them raining out into the ocean, where they supply vital nutrients at the base of the marine food chain and stimulate photosynthetic blooms that both reflect sunlight to space and send carbon to the ocean floor. Some of the dust makes it to the Americas where it mineralizes soils and stimulates growth, while also withdrawing carbon from the atmosphere.

Bamboo, which is endemic in South America, releases 35% more oxygen (O2) to the air than any other plant. Most of that oxygen was originally carbon dioxide (CO2) that the bamboo inhaled. For every O2 molecule it exhales, it is left with a carbon atom. It puts that either into growth or, if it is past its growth season, into the carbon pool below its roots. Bamboo absorbs 4 times more CO2 per area of land each year than trees. Much of the silica that makes up the cells of bamboo and gives it its strength could have been, not long before, sand in the Sahara.

Amok AMOC

Stefan Rahmstorf at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany published an article in Oceanography earlier this year that led with this vignette from early ocean exploration:

In 1751, the captain of an English slave-trading ship made a historic discovery. While sailing at 25°N in the subtropical North Atlantic Ocean, Captain Henry Ellis lowered a “bucket sea-gauge,” devised and provided to him by the British clergyman Reverend Stephen Hales, through the warm surface waters into the deep. By means of a long rope and a system of valves, water from various depths could be brought up to the deck where its temperature was read from a built-in thermometer. To his surprise, Captain Ellis found that the deep water was icy cold.

He reported his findings to Reverend Hales in a letter: “The cold increased regularly, in proportion to the depths, till it descended to 3900 feet: from whence the mercury in the thermometer came up at 53 degrees (Fahrenheit); and tho’ I afterwards sunk it to the depth of 5346 feet, that is a mile and 66 feet, it came up no lower.”

These were the first ever recorded temperature measurements of the deep ocean. They revealed what is now known to be a fundamental and striking physical feature of the world ocean: deep water is always cold. The warm waters of the tropics and subtropics are confined to a thin layer at the surface; the heat of the sun does not slowly warm the depths during centuries or millennia as might be expected.

While this discovery might have had the potential to capture enough solar energy to power a fantastic 18th Century steampunk civilization (imagine no coal-smoked cities, no climate change, no need for military outposts in the Middle East), Ellis and Hales were not Jules Verne. They were in the slave-trading business and their lamps were lit with whale oil. They used their discovery to chill their wine. What interested the scientists of the time was how to account for such cold at Equatorial latitudes.

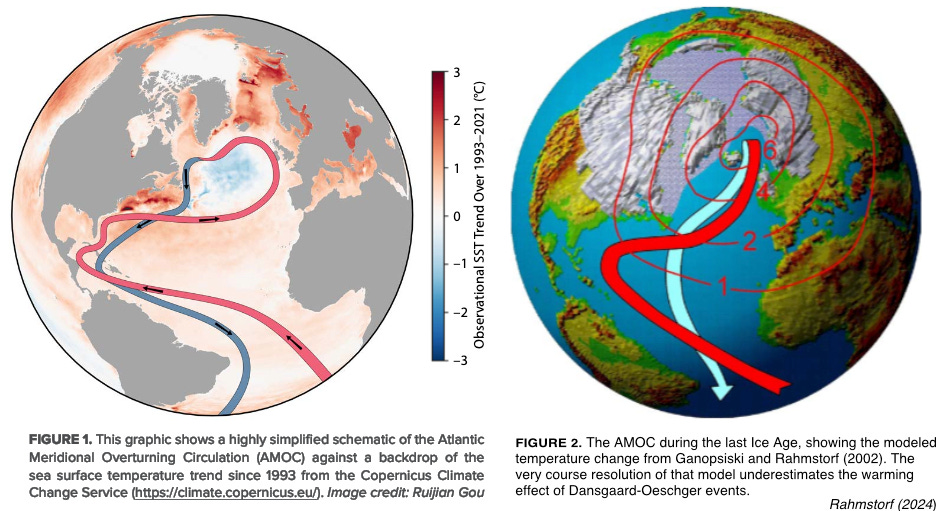

The puzzle would not be explained for another 50 years, when Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, first proposed a northward flow of warm surface waters from the tropics and a deep cold return flow from the Arctic. What we today call the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) was calculated in 2019 to transport one petawatt (1015 Watts) of thermal energy, or about 50 times the energy of all human projects and extractions.

The generous gifting of this warm bonanza made farming and herding in Iceland, Ireland, Scotland, the Nordics, Baltics and the Atlantic provinces of Canada possible and the Western tropical regions rich in forests and human settlement. In the far North, after the retreat of the glaciers, it made a vast territory suitable for human habitation.

Unfortunately, Rahmstorf’s paper is not about being grateful for what the AMOC gives, but what it may soon taketh away. By melting the ice off of the North Pole and Greenland, profligate fossil carbon pollution by humans has changed the salinity and cooling that power AMOC’s engine. As ice melts off the top half of the planet (assuming you are oriented in that direction from space), AMOC has been slowing, and doing so at a quickening pace.

Given the many independent lines of evidence, there is overwhelming evidence for a long-term weakening of the AMOC since the early or mid-twentieth century.

***

The current cold blob is already affecting our weather, though not in the way that might be expected: a cold sub-polar North Atlantic correlates with summer heat in Europe (Duchez et al., 2016). The cooling of the sea surface is enough to influence the air pressure distribution in a way that encourages an influx of warm air from the south into Europe.

In other words, Europe becomes like a loaf of bread baked in a skillet—burnt on the bottom and cold and gooey on top. The last time this happened, toward the end of last Ice Age, it was caused by the breakup of the thick Laurentide Ice Sheet that covered northern America, sending out “iceberg armadas.”

This led to even more dramatic climate changes, linked to a complete breakdown of the AMOC. So much ice entered the ocean that sea levels rose by several meters (Hemming, 2004). Evidence that this amount of freshwater entering the northern Atlantic shut down the AMOC is found in the fact that Antarctica warmed while the Northern Hemisphere cooled (Blunier et al., 1998), indicating that the AMOC’s huge heat transport from the far south across the equator to the high north had essentially stopped.

The Equatorial region retained heat while northern parts of Europe experienced extreme cold. Tropical rainfall belts shifted, leading to warm and humid conditions as far away as Asia, and at intervals, an absence of the Asian monsoons and catastrophic drought. The danger, at least for Anglophiles and Europhiles, is that Iceland, Ireland, Scotland, Denmark and the Netherlands could literally freeze while Southern Europe and the Mediterranean, North Africa, México, the Caribbean Basin and the US Gulf Coast bake. Some models spare Northern Europe, including the Baltics, Norway and Sweden, due to countervailing warming migrating up from Africa and the Mediterranean, but still offer little hope for Ireland and the UK.

Rahmstorf says we likely will get a couple decade advance signal of an imminent shutdown and we have not seen that yet. But it will be too late to stop it once that signal is received.

Some further consequences include major additional sea level rise especially along the American Atlantic coast, reduced ocean carbon dioxide uptake, greatly reduced oxygen supply to the deep ocean, and likely ecosystem collapse in the northern Atlantic.

—Rahmstorf (2024)

Reverse Tipping

But what about the question we started with? Even supposing a slowing or stopping of the AMOC may destroy us, might it not also trigger a rebalancing of the climate? So, for instance, as heat remains in the tropics, might that not also enlarge the volume of airborne dust in the lower atmosphere, bringing both nutrient blooms to the ocean and continents (withdrawing carbon) and also increasing albedo by enhanced cloud reflectivity, changing the balance of solar heating by radiating sunlight back to space before it reaches the planet’s surface? The climate models have so far not been encouraging.

When you experiment on an entire planet (the only one we’ve got, by the way), you may not get to find out the result of your experiments very quickly.

The scary part? You may.

References

Bates, Albert. 1990. Climate in Crisis: The Greenhouse Effect and What We Can Do (Summertown: Book Publishing Co)

Blunier, T., J. Chappellaz, J. Schwander,. A. Dällenbach, B. Stauffer, T.F. Stocker, D. Raynaud, J. Jouzel, H.B. Clausen, C.U. Hammer, and J.S. Johnsen. 1998. Asynchrony of Antarctic and Greenland climate change during the last glacial period. Nature 394:739–743, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/29447.

Boers, N. 2021. Observation-based early-warning signals for a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Nature Climate Change 11(8):680–688, https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41558-021-01097-4.

Broecker, W. 1987. Unpleasant surprises in the greenhouse? Nature 328:123–126, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/328123a0.

Duchez, A., E. Frajka-Williams, S.A. Josey, D.G. Evans, J.P. Grist, R. Marsh, G.D. McCarthy, B. Sinha, D.I. Berry, and J.J.M. Hirschi. 2016. Drivers of exceptionally cold North Atlantic Ocean temperatures and their link to the 2015 European heat wave. Environmental Research Letters 11(7):074004, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/7/074004.

Ellis, H. 1751. A letter to the Rev. Dr. Hales, F.R.S. from Captain Ellis, F.R.S. dated Jan. 7, 1750–51, at Cape Monte Africa, Ship Earl of Halifax. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 47:211–214.

Heinrich, H. 1988. Origin and consequences of cyclic ice rafting in the northeast Atlantic Ocean during the past 130,000 years. Quaternary Research 29:143–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/ 0033-5894(88)90057-9.

Hemming, S.R. 2004. Heinrich events: Massive late Pleistocene detritus layers of the North Atlantic and their global climate imprint. Reviews of Geophysics 42(1), https://doi.org/10.1029/ 2003RG000128.

Rahmstorf, S. 2024. Is the Atlantic overturning circulation approaching a tipping point? Oceanography, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2024.501.

Thompson, B. 1797. The complete works of Count Rumford (1870). Boston, American Academy of Sciences 1:237–400.

Meanwhile, let’s end these wars. We support peace in the West Bank and Gaza and the efforts to bring an immediate cessation to the war. Global Village Institute’s Peace Thru Permaculture initiative has sponsored the Green Kibbutz network in Israel and the Marda Permaculture Farm in the West Bank for over 30 years and will continue to do so, with your assistance. We aid Ukrainian families seeking refuge in ecovillages and permaculture farms along the Green Road and work to heal collective trauma everywhere through the Pocket Project. You can read all about it on the Global Village Institute website (GVIx.org). Thank you for your support.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger, Substack and Medium subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions can be made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration.

當人類被關在籠内,地球持續美好,所以,給我們的教訓是:

人類毫不重要,空氣,土壤,天空和流水没有你們依然美好。

所以當你們走出籠子的時候,請記得你們是地球的客人,不是主人。

When humans are locked in a cage, the earth continues to be beautiful. Therefore, the lesson for us is: Human beings are not important. The air, soil, sky and water are still beautiful without you. So, when you step out of the cage, please remember that you are guests of the Earth, not its hosts.

We have a complete solution. We can restore whales to the ocean and bison to the plains. We can recover all the great old-growth forests. We possess the knowledge and tools to rebuild savannah and wetland ecosystems. It is not too late. All of these great works are recoverable. We can have a human population sized to harmonize, not destabilize. We can have an atmosphere that heats and cools just the right amount, is easy on our lungs and sweet to our nostrils with the scent of ten thousand flowers. All of that beckons. All of that is within reach.