Drey’s Challenge

Many of the financial incentives that stripped the forests of Missouri in 1910 are still present in 2010.

In 1899, the sawmill at Grandin, Missouri, east of the Current River, consumed 70 acres of woodland a day and produced in excess of 250,000 board feet of lumber, lath, and shingles. Many sawmill towns came into existence in rural Missouri around the turn of the century, using river power, animals, or coal to turn the Ozark forests into timber and sawdust. By the 1920s, all but a few acres of Missouri’s virgin forests were gone, the mills were shut down, and all those jobs were lost.

The erosion of the soil was so severe that farming also entered a crisis, and many farmers sold out and left. The streams were choked with silt, and wildlife declined to only about 2000 deer and a similar number of turkeys in the entire state. Eventually, in the 1930s, the federal government bought the barren landscape and sent in the Civilian Conservation Corps to fight fires, build roads, and plant trees.

Among those taking an interest in the Ozark forests was a young businessman named Leo Drey. In 1951, Drey used some of his inheritance from his father’s business, Drey Perfect Mason Jars, to purchase 1407 acres of oak and pine, much of it rotten, for $4 an acre. Drey was 34 years old and a 1939 graduate of Antioch College, whose founder, Horace Mann, had told students, “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.”

Recognizing his own limitations, Drey hired a forestry instructor at the University of Missouri to help him locate and buy forested land. Over the next few years, he expanded his holdings to over 125,000 acres, including a single purchase in 1954 of nearly 90,000 acres from the National Distillers Products Corporation of New York. He called it Pioneer Forest, not only because he intended to manage it as a model of sustainable forestry, but also because Pioneer Cooperage Company of St. Louis had originally assembled the largest tract. Pioneer Cooperage had begun a sustainable harvest of white oak for barrel staves under professional foresters Ed Woods and Charlie Kirk. The company was then sold, in 1948, to National Distillers, with its forestry team intact, but several years later the distilling company decided to liquidate the forest and sell out.

Woods and Kirk alerted Drey, who entered into negotiations to purchase the land and tried to save as much as he could, but National Distillers insisted on the right to cut all white oak over 15 inches in diameter. As Drey and his new forestry team watched helplessly, 12 million board feet of oak were cut in 1954 alone, and another 12 million were lost to the cataclysmic drought and fires of the era.

Much of the forest that Drey, Woods, and Kirk began with was severely degraded, but they maintained long-term records of inventory, species composition, stand volume, and other indicators of systemic health. Important for forest health and productivity, they believed, was to maintain diverse species and ages of trees on every acre. To do that, they practiced uneven-aged silviculture through single-tree selection, marking and taking out the weak, deformed, and crowded trees, and paying careful attention to slope, soil, and canopy openings to favor young reproduction and continued growth of the best trees of varied species and sizes. They were more concerned about what remained than they were about what was removed. They also kept logging equipment out of stream bottoms, maintained forested stream buffers, and rarely cut more than 40 percent of the volume in any given stand.

During the 1960s in the West and South and by the early 1970s in the Ozarks, professional foresters on federal and state forests and in forestry schools shifted to a more intensive commercial model of forestry based on even-aged management by clearcutting. Industrial-scale harvesting equipment often abused the terrain and watercourses. Regeneration or planting favored the most commercially valuable species, often monocultures of hybrids designed for fast growth. For decades, most forestry research, funded by the federal government or private industry, was directed to even-aged management to improve industry profitability. Until recently, little consideration was given to uneven-aged management or to ecosystem health, carbon sequestration, or biodiversity.

Many of the financial incentives that stripped the forests of Missouri in 1910 are still present in 2010. Landowners can get more quick cash by liquidating their forests than by managing them.

The lasting accomplishment of Leo Drey and his small team of foresters was to prove that their uneven-aged management system was both sustainable and profitable. They proved they could secure the natural regeneration of commercially valuable species while also producing a full array of ecological, social, and cultural values.

In 2002, the volume of the standing trees in Pioneer Forest was more than three times what it had been in 1952, and asset value had increased nine-fold since 1972. A 2002 study found that in the previous six years income had exceeded expenses by about 50 percent. For the landowner, the forest had almost certainly been as profitable as it would have been under an even-aged regime. Moreover, once an acre of Ozark forest is clearcut, it requires 80 to 100 years to regrow. During this same period, four or five harvests could be made under the uneven-aged system.

The difference between the two models is more than money, however. Every acre of Pioneer remains a true forest. In studies of salamander populations, microarthropods in leaf litter, black bears, and migrant songbirds, Pioneer Forest wins easily over even-aged forests, and the value for recreation is continual. The average turnover rate for Pioneer’s canopy is 189 to 228 years. Its soils are a rich carbon sink, and it is more resistant to drought, disease, and pest damage than any monocrop plantation could ever be.

The transition to a carbon-aware economy will lead the world away from fossil fuels and into reliance on renewables, including forest biomass. The good news is that sustainable forest ecosystem management may be more economically productive than the industrial tree farms and cattle ranches that replaced wilderness old growth. We can regain wilderness old growth in many parts of the world the way Leo Drey did, and we can do that in a single lifetime.

The above story originally appeared as a chapter in my 2010 book for New Society, The Biochar Solution: Carbon Farming and Climate Change. Leo Drey passed away in 2015 at the age of 98, survived by his wife, their two daughters and a son. The Daily Beast obituary called him “The Lorax of the Ozarks.”

“I get too much credit for doing just what I wanted to do,” said Drey, who was noted for his modesty and soft-spoken manner…. “All I was doing was what came natural; I was trying to put together this demonstration area that would prove you could manage land through individual tree selection and not go broke in the process.”

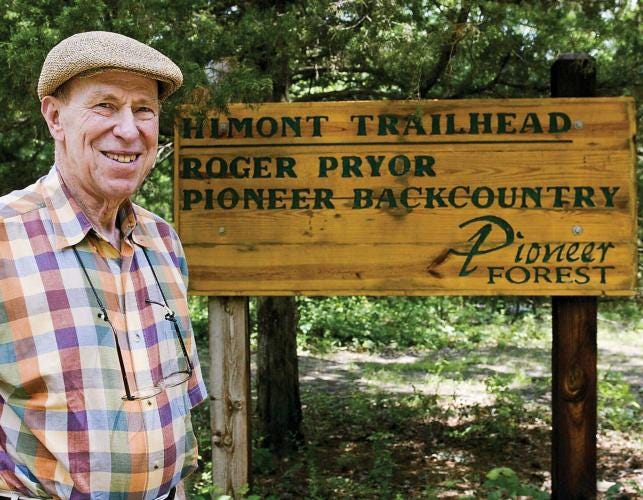

In 2004 Drey and his wife Kay donated the 144,000-acre Pioneer Forest to a Missouri foundation to protect in perpetuity. It is kept open to non-motorized public recreation, including the trails of the Roger Pryor Pioneer Backcountry that Leo hiked into his 70s.

In my previous essays here, I challenged the assumption held by many in the climate action community that forests are an ineffectual strategy to reverse climate change; that they are too vulnerable to wildfire and extreme weather; or that they cannot sequester enough CO2 quickly enough to matter. They can survive the troubles to come, and they will undo a lot of the damage, but they cannot do it alone. They’ll need an entire generation of midwives of entire, intact forest ecosystems. People like Leo and Kay Drey.

Meanwhile, let’s end this war. Towns, villages, and cities in Ukraine are being bombed every day. Ecovillages and permaculture farms have organized something like an underground railroad to shelter families fleeing the cities, either on a long-term basis or temporarily, as people wait for the best moments to cross the border to a safer place or to return to their homes if that becomes possible. There are 70 sites in Ukraine and 500 around the region. As you read this, 24 Ukrainian ecovillages have given shelter to more than 2500 people (up to 500 children) and now host up to 1400 persons (around 200 children). We call our project “The Green Road.”

For most of the children refugees, this will be their first experience in ecovillage living. They will directly experience its wonders, skills, and safety. They may never want to go back. Those that do will carry the seeds within them of the better world they glimpsed through the eyes of a child.

Those wishing to make a tax-deductible gift can do so through Global Village Institute by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by directing donations to greenroad@thefarm.org.

There is more info on the Global Village Institute website at https://www.gvix.org/greenroad or you can listen to this NPR Podcast and read this recent article in Mother Jones. Thank you for your help.

The COVID-19 pandemic destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed climate change, a juggernaut threat to all life, humans included. We had a trial run at emergency problem-solving on a global scale with COVID — and we failed. 6.95 million people, and counting, have died. We ignored well-laid plans to isolate and contact trace early cases; overloaded our ICUs; parked morgue trucks on the streets; incinerated bodies until the smoke obscured our cities as much as the raging wildfires. The modern world took a masterclass in how abysmally, unbelievably, shockingly bad we could fail, despite our amazing science, vast wealth, and singular talents as a species.

Having failed so dramatically, so convincingly, with such breathtaking ineptitude, do we imagine we will now do better with climate? Having demonstrated such extreme disorientation in the face of a few simple strands of RNA, do we imagine we can call upon some magic power that will arrest all our planetary-ecosystem-destroying activities?

As the world emerges into pandemic recovery (maybe), there is growing recognition that we must learn to do better. We must chart a pathway to a new carbon economy that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backward — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience. We must lead by good examples; carrots, not sticks; ecovillages, not carbon indulgences. We must attract a broad swath of people to this work by honoring it, rewarding it, and making it fun. That is our challenge now.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

Thank you for reading The Great Change.