Ecosystem Restoration in Lower Manhattan

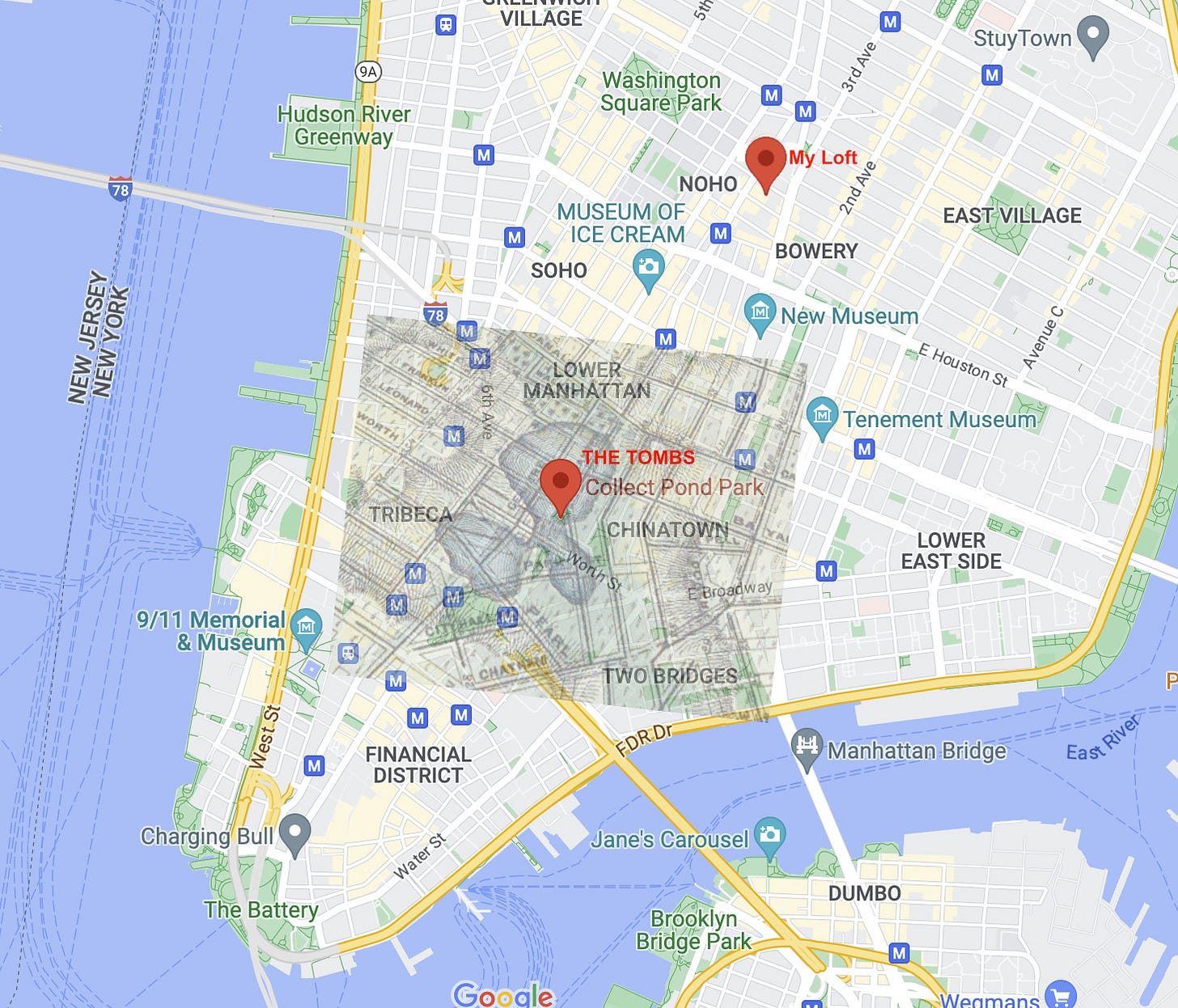

The smartest move the city has made yet is creating Collect Park near where the village of Werpoes once stood.

As a grad student, I had little appreciation for the historicity of where I lived or I might better have appreciated some of the ironies and synchronicities that would play out later.

In 1970, I managed to rent a fifth-floor walk-up with a freight elevator at 47 Great Jones Street, between Bowery and Lafayette, in lower Manhattan. I had to first remove the old sewing machines and product racks before I could start making the former stuffed-toy company into a loft. I inserted a shower, kitchenette, and three bedrooms into the 6900 square foot factory floor. My rent was $1050 per month, but with two roommates it became affordable for working students. The National Lampoon took the floor above me and LaMama Dance Studio practiced on the hardwood floors below.

Since at least the late 18th century, and possibly 150 years earlier, nearly every male ancestor in my father’s line had some connection to New York City. The earliest I can document is Issachar Bates who was with George Washington at Bunker Hill. His grandson Artemus enlisted with the Union Army recruiting office here. On my mother’s side, my grandfather and grandmother lived in the city during the time she was a mezzo-soprano with the New York Met and he was going to medical school. For most of my youth, my dad was a public relations account manager at big-name agencies, one of the original Mad Men. Apart from commuting with friends to visit McSorley’s Olde Ale House when I was too young to drink in Connecticut, my deepest dive into New Yorkness was the three years I spent attending law school.

This Great Jones low-rise was built in 1845. Among the artifacts I uncovered were letterhead stationary and packs of British needles crafted by the Brabant Needle Company that had moved to New York in 1900. To stay marginally legal with the city I christened my artist loft “Brabant Needle Studio.”

In 2022, a similar loft in a nearby building was subdivided into three 2300 sq. ft. walk-ups and one of those apartments was sold for $4.3 million. The building’s co-op pays no property tax because it is a rent-controlled restored historic property. Residents pay the same $1050 that my roommates, Tom and Agneta, and I did in 1970, as monthly co-op “maintenance.”

That loft is now for sale again, and some NYC bank will finance it on a 30-year mortgage with $860,000 down and $23,134 per year (adjustable). With a mortgage payment of less than $2000 per month and a monthly maintenance fee of $1050, that is darn cheap rent for a prime Noho location. The cumulative appreciation rate of Manhattan real estate over the past ten years has been 38.81%, giving the purchase price a better ROI than most other investments. There were no purchase prices in 1970; it was a straight lease.

The Bowery

The Dutch had a tendency to assign American Indian names to people and places but the trail from the South coast of the island that ran up its center they named “the Bowery” for its flowery tree arches and the Dutch bouwerij (farms) that sprang up in the fertile soil along its path. The Munsee Lenape called it the Wickquasgeck—“trail to the wading place”—which likely referred to The Collect, a 48-acre spring-fed pond that gathered water from a dozen hillsides and released it only grudgingly to the Hudson and East Rivers. Fish were so abundant in the pond you could net them just by wading a short distance. It was but a small part of the inland cultivated ecology created to nourish and sustain the Lenape over millennia.

The Collect is emblematic of European conquest of the Americas or what William Catton called “Homo Colossus”

When the earth's deposits of fossil fuels and mineral resources were being laid down, Homo sapiens had not yet been prepared by evolution to take advantage of them. As soon as technology made it possible for mankind to do so, people eagerly (and without foreseeing the ultimate consequences) shifted to a high-energy way of life. Man became, in effect, a detritivore, Homo colossus. Our species bloomed, and now we must expect a crash (of some sort) as the natural sequel.

— Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change (1980 p. 170).

By the time New Amsterdam was handed off to the English in 1664, much of the natural ecology of the island remained intact, although a significant dent had already been put into the Lenape’s most valuable food supply—the oyster beds. The Bowery was well-established as the primary route out of the city, connecting through Dutch Harlem on the North shore to what later became known as the Boston Post Road. When New York was the capital of the independent United States (1785 until 1790), the Congress’s presiding officer, George Washington, lived a few-minute walk from my loft, at the corner of Rose and Pearl Streets. Prior to the Dutch, the sparkling clear pond supplied Munsee villages with copious amounts of fish. While it had been already fished out by the time of Independence, The Collect (Dutch: “kolch,” or “small body of water”) was New York’s main source of drinking water.

The pond occupied approximately 48 acres (190,000 m2) and was as deep as 60 feet (18 m). Fed by an underground spring, it was located in a valley, with Bayard Mount (at 110 feet or 34 meters, tallest hill in lower Manhattan) to the northeast and Kalck Hoek (Dutch for Chalk Point, named for the numerous oyster shell middens left by the indigenous Native American inhabitants) to the west. A stream flowed north out of the pond and then west through a salt marsh (which, after being drained, became a meadow by the name of "Lispenard Meadows") to the Hudson River, while another stream issued from the southeastern part of the pond in an easterly direction to the East River.

The Collect was so large that John Fitch and Robert Fulton used it to test the world’s first steam-powered paddlewheel boat in 1796.

In the 18th century, the pond was used as a picnic area during summer and a skating rink during the winter. Beginning in the early 18th century, various commercial enterprises were built along the shores of the pond in order to use the water. These businesses included Coulthards Brewery, Nicholas Bayard's slaughterhouse on Mulberry Street (which was nicknamed "Slaughterhouse Street”), numerous tanneries on the southeastern shore, and the pottery works of German immigrants Johan Willem Crolius and Johan Remmey on Pot Bakers Hill on the south-southwestern shore. By the late 18th century, the pond was considered "a very sink and common sewer.”

A neighborhood known as Paradise Square soon arose over the pond’s previous site. Unfortunately, due to the area’s extremely high water table, Paradise Square began to sink in the 1820’s. The neighborhood also began to emit a foul odor, prompting the most affluent residents to leave the community. By the 1830s, Paradise Square had become the notorious “Five Points,” an extremely poor and dangerous neighborhood renowned for its crime and filth.

— New York Parks Department

In his Goodreads review of Ishmael by Daniel Quinn, my friend Randall Wallace said it made him think of modern Taker culture, as the original “effluent” society:

When Ishmael said, “we know what happens if you take the taker premise, that the world belongs to man….” A Taker bumper sticker would say, “Consuming the World.” A Leaver bumper sticker wouldn’t say anything, because they wouldn’t have a car.

Quinn himself had Ishmael say:

There's nothing fundamentally wrong with people. Given a story to enact that puts them in accord with the world, they will live in accord with the world. But given a story to enact that puts them at odds with the world, as yours does, they will live at odds with the world. Given a story to enact in which they are the lords of the world, they will ACT like lords of the world. And, given a story to enact in which the world is a foe to be conquered, they will conquer it like a foe, and one day, inevitably, their foe will lie bleeding to death at their feet, as the world is now.

― Daniel Quinn, Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit

Pierre Charles L'Enfant proposed cleaning the pond and making it a centerpiece of a recreational park, around which the residential areas of the city could grow. His proposal was rejected, and it was decided to drain and fill in the pond. The 1811 infill created swampy, mosquito-ridden conditions, which the city deemed ideal for the location of a jail, nicknamed "The Tombs," built on Centre Street in 1838 on the site of the former pond.

The Tombs

The jail was constructed on a huge platform of hemlock logs in an attempt to give it secure foundations but it began to subside almost as soon as it was completed and was notorious for leaks in the lower floors when it rained. It was replaced in 1902 with a new one on the same site connected by the "Bridge of Sighs" to the Criminal Courts Building on the Franklin Street side, where prisoners, often in manacled chain gangs, would be herded to their arraignments (named after the original Bridge of Sighs connecting Venice’s prison to the torture chambers in the Doge’s Palace). In a 1902 facelift, large concrete caissons were laid on bedrock 140 feet below street level and the holding cells with as many as 30 each were sited in the subterranean floors. Little of that arrangement changed when the Tombs was moved across Centre Street in 1941.

By 1969, the Tombs ranked as the worst of the city's jails, both in overall conditions and in overcrowding. It held an average of 2,000 inmates in spaces designed for 925. Lawsuits and riots pointed to the perennial flooding every time it rained. The new intake was forced into standing-room-only cells in ankle-deep water. Following the 1970 riot, Mayor John Lindsay had the primary troublemakers shipped upstate to the state's Attica Correctional Facility which likely contributed to the Attica Prison riot about a year later.

Crime was only one half of the story in the “Five Points:” the high population density of the neighborhood and the existence of a subterranean swamp precipitated the outbreak of disease. Throughout the nineteenth century, nearly all of the city’s cholera outbreaks originated in this neighborhood.

—New York Parks Department

Paul Simon's song "Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard" includes a threat of being placed in the "House of Detention.” That was The Tombs. In my second year at Law School, I took a job with the NY Appellate Division that was attempting to reduce the jail’s population. My fellow law students and I would interview arrestees to determine if they had enough ties to the community so as to pose no flight risk and be released “on recognizance” (ROR).

Such indecent and disgusting dungeons as these cells, would bring disgrace upon the most despotic empire in the world!

— Charles Dickens, American Notes (1842)

Of course, I knew nothing then about The Collect as I biked to and from work down Bowery every day. I saw the rain coming from the ceilings and how some corridors would become “trails to the wading place.” One day I witnessed a cruel and brutal beating of a handcuffed and manacled prisoner by two corrections officers as I rode with them in the elevator between the cells and the courtrooms. I reported the names of the officers when I relayed the incident to my supervisor but when the formal complaint went through channels I was summoned to the ninth floor.

The office of the District Attorney had splendid picture window views of lower Manhattan at night. With a wall of law reporter volumes at his back, the D.A. was very cordial but advised me that my complaint would not result in any disciplinary action for the officers involved. He wanted to know if I planned to sue and urged me to consider my career advancement, all the good that our program was doing, and how badly things could turn if we Appellate Division ROR investigators were to get cross-ways with Corrections Department rank and file. In other words, sit down and shut up and just do your job.

I didn’t have any interest in career advancement and anyway, that summer I had plans to hitchhike around Europe, so I quit rather than shake up the ROR detente with officers. The city decided to close the Tombs two years later. After a hiatus in Brooklyn, the Centre Street complex was remodeled and reopened in 1983. It was closed again in 2020 for all the same reasons. Another remodeling is underway and the city hopes to reopen later this year with a Tombs capacity of 886 beds. Perhaps they will be water beds.

Once you learn to discern the voice of Mother Culture humming in the background, telling her story over and over again to the people of your culture, you’ll never stop being conscious of it. Wherever you go for the rest of your life, you’ll be tempted to say to the people around you, “How can you listen to this stuff and not recognize it for what it is?”

― Daniel Quinn, Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit

Nature never understands when humans try to move a river or a lake. It is always doomed to failure. Ask the Corps of Engineers. Just because they infilled the Collect doesn’t mean they changed the hydrogeomorphology of artesian Manhattan. Those beaten-down hills still drain, subtly below surface, to The Collect and thence to the Hudson and East Rivers.

The squalid conditions of the “Five Points” soon began to end after the 1890 publication of How the Other Half Lives, by Jacob Riis (1849-1914). Riis’ work was a revealing account of slum life on the Lower East Side that disturbed late-nineteenth century reformers. Within four years of the book’s appearance, the City of New York had condemned nearly all the tenements that comprised the area, ridding the community of crime and filth. This revived area is now known as Civic Center, due to the presence of many governmental offices.

—New York Parks Department

Am I the only one who sees irony in all city, state and federal government offices being relocated to a literal swamp? Notable progeny of Five Points were Al Capone, Lucky Luciano and Boss Tweed, all of whom spent time in The Tombs, close to their childhood homes.

The smartest move the city has made lately has been to create Collect Park on the block bordered by Lafayette Street, Leonard Street, Centre Street, and White Street, at the approximate center of the pond. (40.7163°N 74.0019°W) The Munsee village on the near shore had been called Werpoes. In 2012, construction of the park uncovered the original granite foundation of The Tombs, leading to a partial stop-work order pending archaeological investigation. The newly rebuilt park re-opened in May 2014 and included a water feature—a reflecting pool— evocative of the former Collect. While you can’t really call it a pond, and the only paddlewheels on it are toys, it is yet conceivable that it could be enlarged enough—some day—to drain The Tombs.

This would be a real case of “draining the swamp.”

Meanwhile, let’s end this war. Towns, villages, and cities in Ukraine are being bombed every day. Ecovillages and permaculture farms have organized something like an underground railroad to shelter families fleeing the cities, either on a long-term basis or temporarily, as people wait for the best moments to cross the border to a safer place or to return to their homes if that becomes possible. There are 70 sites in Ukraine and 500 around the region. As you read this, we are sheltering some 2,000 adults and 450 children. We call our project “The Green Road.”

For most of the children refugees, this will be their first experience in ecovillage living. They will directly experience its wonders, skills, and safety. They may never want to go back. Those that do will carry the seeds within them of the better world they glimpsed through the eyes of a child.

Those wishing to make a tax-deductible gift can do so through Global Village Institute by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by directing donations to greenroad@thefarm.org.

There is more info on the Global Village Institute website at https://www.gvix.org/greenroad or read this recent article in Mother Jones. Thank you for your help.

The COVID-19 pandemic destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed climate change, a juggernaut threat to all life, humans included. We had a trial run at emergency problem-solving on a global scale with COVID — and we failed. 6.88 million people, and counting, have died. We ignored well-laid plans to isolate and contact trace early cases; overloaded our ICUs; parked morgue trucks on the streets; incinerated bodies until the smoke obscured our cities as much as the raging wildfires. The modern world took a masterclass in how abysmally, unbelievably, shockingly bad we could fail, despite our amazing science, vast wealth, and singular talents as a species.

Having failed so dramatically, so convincingly, with such breathtaking ineptitude, do we imagine we will now do better with climate? Having demonstrated such extreme disorientation in the face of a few simple strands of RNA, do we imagine we can call upon some magic power that will arrest all our planetary-ecosystem-destroying activities?

As the world emerges into pandemic recovery (maybe), there is growing recognition that we must learn to do better. We must chart a pathway to a new carbon economy that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backward — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience. We must lead by good examples; carrots, not sticks; ecovillages, not carbon indulgences. We must attract a broad swath of people to this work by honoring it, rewarding it, and making it fun. That is our challenge now.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

Thank you for reading The Great Change.