Foggy Forecasts for Clean Energy Futures

Can we build out renewable energy fast enough to avoid some nasty tipping points?

In my two previous posts, I looked at two aspects of the Hansen et al pre-print, Global Warming in the Pipeline, forecasting the course of climate change this century from paleoclimate record and atmospheric aerosols. I have been trying to de-jargon the science and take it into the real world. In his own attempt to demystify and disarm his critics, Hansen writes to his newsletter subscribers:

Twitter-World “science.” We have been told that a bizarre criticism of the Pipeline paper appeared on Twitter, concluding that our paper was “wrong,” because we did not consider that GHGs in the atmosphere would soon be declining as human emissions decrease and the ocean and atmosphere absorb the human-made increase of GHGs.

We hope that even the non-scientist can see through such thinking. When Charney defined the gedanken problem: what is the equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) to 2×CO2 forcing, he knew that keeping CO2 fixed at that level and fixing certain boundary conditions such as ice sheet size was an idealized situation designed to help develop an understanding of climate change and climate feedbacks. Our conclusion that ECS is at least ~4°C, near the upper end of Charney’s estimated range, refers to that specific problem. Our study does more than that, however, we also address the delay in the climate response caused by the ocean’s thermal inertia. With the help of Earth’s paleoclimate history, we also address the question: what is Earth System Sensitivity (ESS) for the idealized case in which 2×CO2 forcing is kept constant until all fast and slow feedbacks are allowed to reach equilibrium. The answer we find is close to 10°C, for CO2 forcing alone. If we include the negative forcing by today’s aerosols, the response may be as low as 6-7°C, but ESS is ~10°C.

This is still a bit obscure. Hansen’s key finding is in the last two sentences—once carbon dioxide in the atmosphere crosses into the territory of double pre-industrial levels (which the world did in 2022) Earth’s average temperature will increase by 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit). Earth’s average temperature is 13.9 °C (57°F). It has risen by 0.08°C (0.14°F) per decade since 1980. Achieving equilibrium with CO2 today would rise the temperature of Earth to 24 degrees, 72% higher than today. In contrast, consider that we are only 5 degrees, or 36%, warmer today than in distant ice ages. So, take that heating out twice as far as it went in the past 20,000 years and you can imagine what some now living may experience in this lifetime.

Hansen points out that we are already past doubling for CO2 once you include all the other trace gases. Methane, for instance, has 84 times the potency of CO2 as an atmospheric insulator in the first 20 years but is transformed to less potent CO2 over a century, diminishing the average impact to about 28 times the potency of CO2. Atmospheric methane has increased 262% since pre-industrial times, to 1908 ppb, but since the start of the pandemic has been adding 18 ppb/y, double its historical rate.

When the climate changes that quickly we’d like to know what the most likely outcomes are going to be for us. As I write this, there are thousands of incredibly knowledgeable and intrepid researchers around the world running complicated AI climate simulations through advanced supercomputers whose processing speeds are accelerating all the time. Their answers get better by the week and day, and the questions get more sophisticated. More and more data is being fed in from field instruments and newer generations of satellites and depth buoys—everything from seawater salinity to permafrost melt, and fugitive methane from pipelines and abandoned wells to the sunlight reflectivity of urban sprawl.

In December 2022 scientists at the Potsdam Institute for climate research in Germany teamed up with the Washington Post to produce a fascinating analysis of more than 1200 different scenarios in an attempt to establish whether any of them might actually keep global warming below 1.5 degrees by the end of the century.

The Potsdam team applied five key criteria to make their assessment.

The rate of acceleration in technologies like direct air capture (DAC) and bioenergy with carbon capture (BECCS).

The rate of acceleration in agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU).

Potential future carbon intensity of energy production.

Potential changes in the global level of demand for energy itself.

Trends in non-CO2 emissions, predominantly methane.

Then in 2022, the IPCC published its Sixth Assessment, Working Group 3 Report (with an ecovillage on the cover) that contained another 1202 potential future pathways. Both Potsdam and IPCC concluded, ominously, that the vast majority of projections predict increases far higher than 1.5°C by 2100.

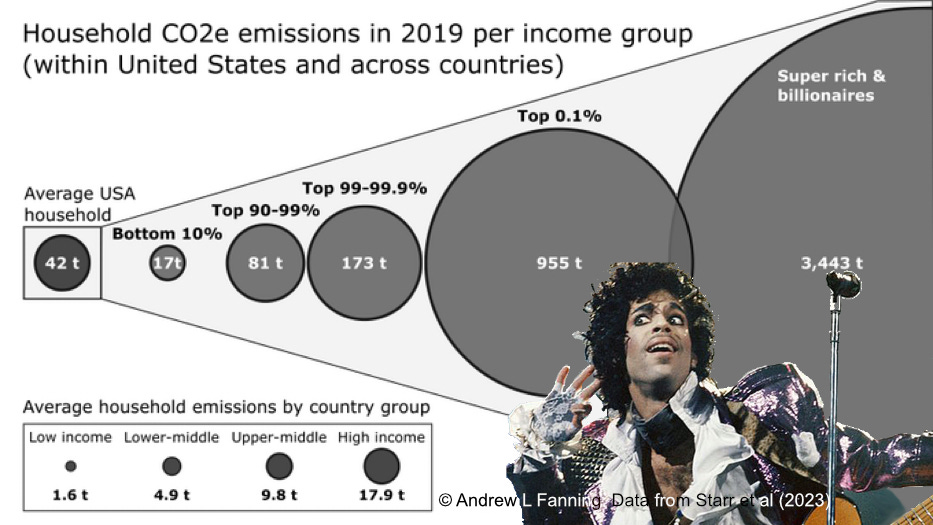

Most of the predictions push us up to somewhere between two and three degrees of warming where it would no longer be possible to maintain global civilization as we know it today, and the worst take us above 5 degrees and human extinction by the end of the century. Ninety-five percent of humanity is completely unaware of this and the 5% who are aware still party like it’s 1999 (in 1982).

The overwhelming scientific consensus is that we are suicidally stupid, but for sake of argument, let's suppose we aren’t. Maybe we are just ignorant. Suppose we suddenly awaken to the threat and look up?

Bending the Curve

The Potsdam and Washington Post teams highlighted 230 of the original 1202 scenarios that—while vanishingly unlikely—would bend the curve enough to allow us an escape. Global emissions fell by about five percent during the pandemic and if we just held that course for the remainder of the century it could mark a pathway out of the dilemma.

I say “vanishingly unlikely,” based on numbers from globalcarbonbudgetdata.org showing emissions jumped back up in 2022. We are now back on the same pre-pandemic trajectory, so any scenarios predicting a dramatic fall in emissions by 2025 or 2030 look hopelessly unrealistic. Moreover, if you mention climate change to the average person on the street in China, India, Thailand, Latin America, or Africa, it is likely you will just get a blank stare. They don’t have any idea what you are talking about.

The Potsdam team then said there remain 112 Pathways that fall into two distinct categories: those that predict what's known as a “high overshoot” before temperatures drop back down again and those that predict a “low overshoot” or even no overshoot at all. High overshoot involves traversing unpleasant tipping points like killing all the polar bears, tripling methane from permafrost, and burning away the Amazon rainforest. Hoping that we might get away with overshoot by employing some kind of as yet unproven silver bullet technologies—artificial trees or artificial plankton—a bit further down the line is arguably delusional and probably suicidal.

One part per million (ppm) CO2 in the atmosphere is equivalent to 2.12 billion tons of carbon (GtC). Thus, an excess of 280 ppm accumulated in the atmosphere since we went from wood to coal and oil means there are (2.12 x 280) 600 billion tons too much that will remain up there for many centuries. Think of a wall of compressed seaweed 1 km high, 1 km wide, and 6000 km long. When the expert researchers looked at the 26 pathways that assume our ability to withdraw and permanently store that carbon they came to the conclusion that the world will most likely run out of all the easy options by 2025 or 2030. Avoiding the nastiest tipping points between now and mid-century will require the removal of something like 2 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere every year by the end of this decade and doubling and tripling that rate in the out years.

Accomplishing this removal by artificial forests (DACCS) will require a lot of additional, renewable energy, but there is another snag. We are already depending on a lot of additional, renewable energy to replace dirty coal and nuke plants, automobiles and gas cooking ranges.

Can we build out renewable energy fast enough to avoid those nasty tipping points? What would that imply for the consumer lifestyles of a large and still growing human population? Would it necessarily imply that population will shrink, that consumerism will implode, or that our expectations for future cities built over rising oceans or colonies on Mars are either wildly unsustainable or delusional? We will look more closely at those questions next week.

References

Hansen, James E., Makiko Sato, Leon Simons, Larissa S. Nazarenko, Karina von Schuckmann, Norman G. Loeb, Matthew B. Osman et al. "Global warming in the pipeline." arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.04474 (2022).

Steffen, Will, Johan Rockström, Katherine Richardson, Timothy M. Lenton, Carl Folke, Diana Liverman, Colin P. Summerhayes et al. "Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 33 (2018): 8252-8259.

Stoddard, Isak, Kevin Anderson, Stuart Capstick, Wim Carton, Joanna Depledge, Keri Facer, Clair Gough et al. "Three decades of climate mitigation: why haven't we bent the global emissions curve?." Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46, no. 1 (2021): 653-689.

Meanwhile, let’s end this war. Towns, villages and cities in Ukraine are being bombed every day. Ecovillages and permaculture farms have organized something like an underground railroad to shelter families fleeing the cities, either on a long-term basis or temporarily, as people wait for the best moments to cross the border to a safer place, or to return to their homes if that becomes possible. There are still 70 sites in Ukraine and 300 around the region. They are calling their project “The Green Road.”

The Green Road is helping these places grow their own food, and raising money to acquire farm machinery and seed, and to erect greenhouses. The opportunity, however, is larger than that. The majority of the migrants are children. This will be the first experience in ecovillage living for most. They will directly experience its wonders, skills, and safety. They may never want to go back. Those that do will carry the seeds within them of the better world they glimpsed through the eyes of a child.

Those wishing to make a tax-deductible gift can do so through Global Village Institute by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by directing donations to greenroad@thefarm.org.

There is more info on the Global Village Institute website at https://www.gvix.org/greenroad

The COVID-19 pandemic destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed climate change, a juggernaut threat to all life, humans included. We had a trial run at emergency problem-solving on a global scale with COVID — and we failed. 6.7 million people, and counting, have died. We ignored well-laid plans to isolate and contact trace early cases; overloaded our ICUs; parked morgue trucks on the streets; incinerated bodies until the smoke obscured our cities as much as the raging wildfires. We set back our children’s education and mental health. We virtualized the work week until few wanted to return to their open-plan cubicle offices. We invented and produced tests and vaccines faster than anyone thought possible but then we hoarded them for the wealthy and denied them to two-thirds of the world, who became the Petri-plates for new variants. SARS jumped from people to dogs and cats to field mice. The modern world took a masterclass in how abysmally, unbelievably, shockingly bad we could fail, despite our amazing science, vast wealth, and singular talents as a species.

Having failed so dramatically, so convincingly, with such breathtaking ineptitude, do we imagine we will now do better with climate? Having demonstrated such extreme disorientation in the face of a few simple strands of RNA, do we imagine we can call upon some magic power that will change all that for planetary-ecosystem-destroying climate change?

As the world emerges into pandemic recovery (maybe), there is growing recognition that we must learn to do better. We must chart a pathway to a new carbon economy that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backward — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience. We must lead by good examples; carrots, not sticks; ecovillages, not carbon indulgences. We must attract a broad swath of people to this work by honoring it, rewarding it, and making it fun. That is our challenge now.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration

Subtitle: "Can we build out renewable energy fast enough to avoid some nasty tipping points?"

When we take the Heinberg Pulse and the Michaux Monkeywrench into account, this question is revealed to be a very strange one, indeed. It's like asking, "Can we save a drowning man by chaining his ankles to a two hundred pound block of underwater concrete?"

For an explanation, see:

Energy Transition & the Luxury Economy

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2022-10-31/energy-transition-the-luxury-economy/

The mainstream / conventional / ubiquitous story of 'energy transition' is one of maintaining urban-industrial-technological (high energy and materials) 'civilization' in a shape familiar to those who live in the global North (rich world). It's purpose -- this story -- is to comfort the comfortable and keep us all from changing course in the direction we ought to be moving in -- which is in the direction of a dramatic and rapid voluntary energy descent (and materials descent, and GDP/GWP descent).

Industrial civilization as we know it will not and cannot continue. Nor will the luxury-dependent modern economy. And what we ought to be doing is recognizing that we're going to have to rapidly reverse the urbanization demographics trend of the last century -- moving as many of us into rural self-provisioning villages as possible, as quickly as possible. Why? Mainly because the only way most folks now living in cities will have a means of livelihood in a post-carbon, low exosomatic energy intensity economy (which is not a luxury economy) will be in a community self-provisioning, agrarian, rural village economy not dependent on the present dominant globalized luxury economy.

There is simply no possible way to maintain the energy intensity of the present dominant world economy system, and that means billions of people will have to leave cities to live in rural villages -- because cities cannot be economically sustained in the near future. They are simply too densely populated for there to be sufficient food growing land to sustain them. The future economy will be a needs based economy, not a luxury economy, and so cities will be few and largely emptied out of people.