Peter Minuit and the Gift Economy

When the Dutch “purchased” Manhattan for $26 in beads, it was a big misunderstanding.

Burning Man forbids exchange of money (except for ice, coffee, and tickets to the event itself) and encourages reliance on a gift economy. In the District of Columbia, it is still illegal to sell marijuana or grow it for sale or barter, but possession and cultivation for gift or personal purposes is legal. A similar gift economy of legal cannabis is emerging in Vermont. It had been realized in Oregon, California, Maine and Massachusetts prior to full legalization.

Something that cannot be sold cannot be commodified. It is like that with commons. If ever they are commodified, they cease to be commons. Commons are inclusive rather than exclusive. Ownership is wide, not narrow. The goal is not to obtain a private yield or profit, but preservation of social and ecological capital. In the case of gifts, it is the preservation of relationships. With commons, it is land. Any notion of return on capital is antithetical. And just as they are received—as a shared inheritance—so there arises the duty to pass the commons on to future generations in at least the same condition as received although, in many indigenous practices, improvement by each generation is the norm.

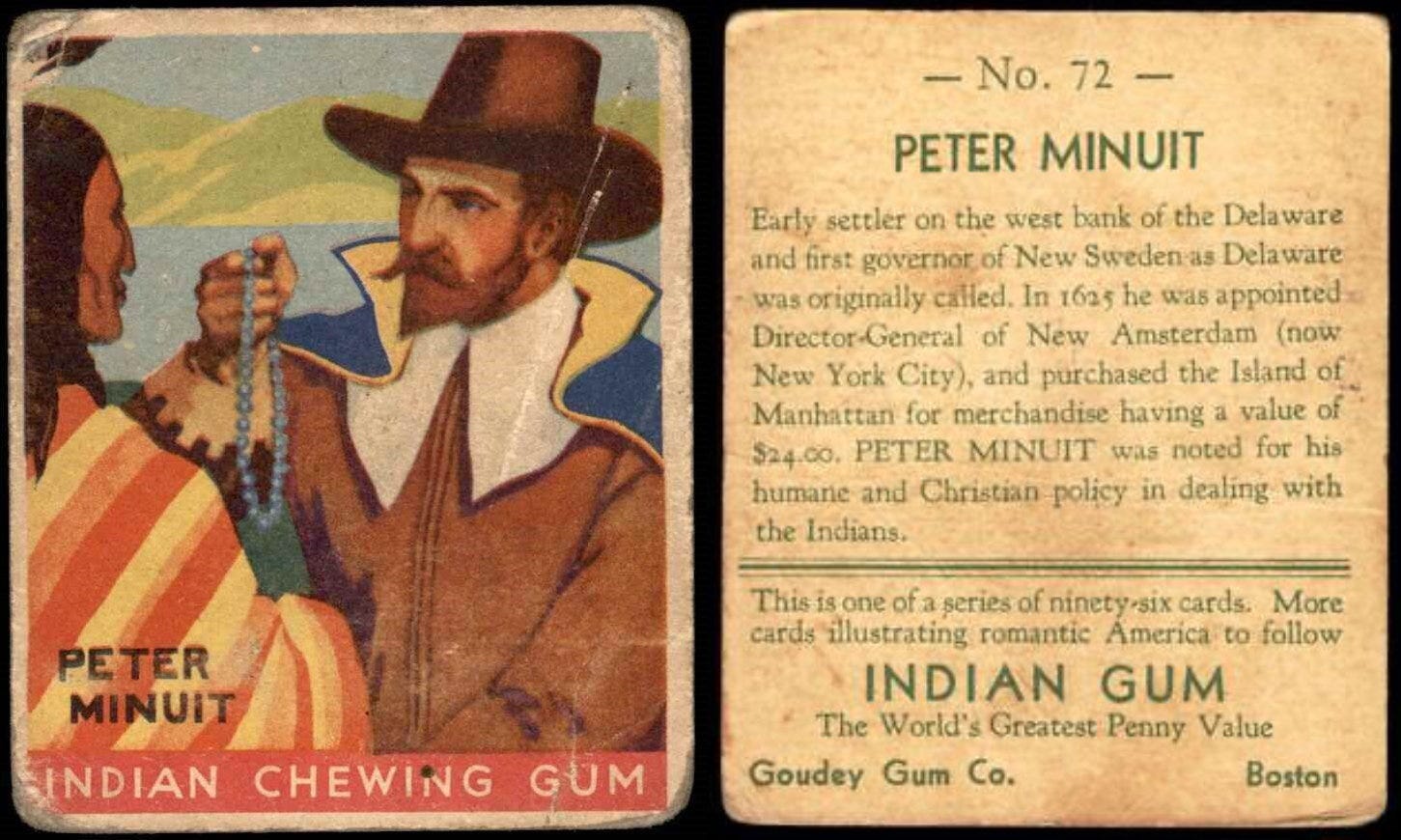

When Peter Minuit boarded a ship bound for New Netherlands in May of 1626, his goal as a director for the Dutch West India Company was not preservation, regeneration or improvement, but extraction for profit.

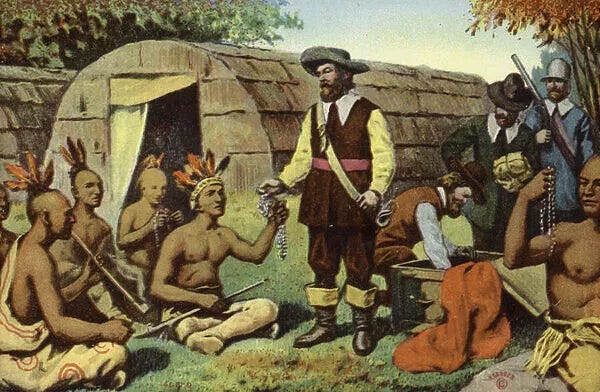

Minuit at first explored the upper reaches of the Hudson and south to the Delaware to establish relations with the indigenous occupants in hopes of bettering trade. It was common, as a trade envoy, to gift trade goods — steel knives, fine ceramic beads, silks and other wovens, whiskey and gunpowder — much in the same way a salesman today gives out samples at trade shows.

To the Dutch, to keep the gift and not give another in exchange would be reprehensible. In a gift economy, the practice was to regard these gifts as peace offerings. “Reciprocity” meant that gifts were to be shared or passed along. "In folk tales," Lewis Hyde remarks, "the person who tries to hold onto a gift usually dies."

The late David Graeber argued that religious traditions of charity and gift-giving emerged almost simultaneously during the "Axial age" (800 to 200 BCE), when coinage was invented and market economies were established on whole continents.

Graeber argues that these charity traditions emerged as a reaction against the nexus formed by coinage, slavery, military violence and the market (a "military-coinage" complex). The new world religions, including Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Christianity, and Islam all sought to preserve "human economies" where money served to cement social relationships rather than purchase things (including people).

In contract jurisprudence, there are doctrines of “mutuality of consideration,” and a “meeting of the minds.” The average New Yorker, and particularly anyone involved in either real estate or finance, will likely tell you that (a) the Dutch purchase of Manhattan for 50 guilders ($26 dollars or ~$963 today) was the greatest land deal of all time, and (b) the Indians who sold the island were the biggest fools ever. Neither proposition is true.

Part (a) is false because any contract lacking either mutuality of consideration or a meeting of the minds is null and void. It also cannot be upheld because it was not “parole,” meaning written, as was and is required for legal transactions involving land. Part (b) is false because, as Minuit knew from his journeys in the North and trades with Iroquois and Huron peoples, trust may be established by gifts, but no more. People who occupy a commons have no more legal authority to alienate their rights than do some to seize and occupy to the exclusion of previous occupants. Minuit was a con man, a Trumpster. The Manhattan deal was a fraud.

When the Dutch appropriated native lands they did not purchase deeds. They issued notes of registry for what was thereafter called “Christian Patented Land.”

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer writes:

In the settler mind, land was property, real estate, capital, or natural resources. But to our people, it was everything—identity, the connection to our ancestors, home to our non-human kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library, the source of all that sustained us. Our lands were where our responsibility to the world was enacted—sacred ground. It belonged to itself. It was gift, not a commodity, so it could never be bought or sold.

Are there any remaining peoples to whom rightful title should revert? There certainly are. Manhattan’s inhabitants were part of a federation of nations, collectively referred to as the Lenapehokink.

Last week we mentioned the Munsiiw (Munsee), who lived in Lower Manhattan. There were at least 21 other bands and tribes in and around New York Harbor, the Jersey Shore, and Long Island Sound— Tappan, Haverstraw, Hackensack, Navasink, Raritan, Unami, Wecquaesgeek, Sintsink, Kitchawank, Nochpeem, Siwanoy, Tankiteke, Wappinger, Canarsee, Manhattan, Matinecock, Massapequa, Merrick, Rockaway, Secatoag and Metoac.

Under Minuit's reign of terror, they surrendered their homes under duress. If captured by the Dutch, adults and children were sold as slaves to sugar plantations in the West Indies or Dutch-occupied Curaçao.

Some Lenapehokink crossed the Hudson to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania where they were welcomed by William Penn and his Quaker brethren. Treaties between Penn and Lenape Chief Tamanend recognized their mutual standing as independent peoples. There is a statue of Tamanend in Philadelphia today. Some Lenapehokink settled in the Pocono Mountains and others in Allentown, Nazareth, and Bethlehem. Others went north to join the Haudenosaunee or the Mohicans.

Later state governments were less obliging. Pennsylvania never formally acknowledged Lenapehokink sovereignty the way Wisconsin, Oklahoma, New Jersey, Delaware, and Canada eventually did. It is a wonder any survived the removals, genocide, and century of slavery that followed American independence. Nonetheless, a Ramapough Lenape was invited to give opening remarks at the United Nations Indigenous Peoples Summit in Geneva in 2002.

Today the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania says on their website:

Ever since our people were fractured by colonialism, there have been Lenape people spread across the country, continent, and beyond. We are not the only nation of Lenape people today; other nations of Lenape people represent both the Lenape who remained in our homeland and our diaspora, and carry on Lenape tradition and culture today.

The late E.O. Wilson, in his modest proposal to rewild half the planet, Half-Earth, wrote:

Leading Anthropocene enthusiasts seem unconcerned with what the consequences will be if their beliefs are played out. They are as free of fear as they are of facts. Of them, the social observer and conservationist Eileen Crist has written:

“Economic growth and consumer cultures will remain the leading social models (many Anthropocene promoters see this as desirable, while a few are ambivalent); we now live on a domesticated planet, with wilderness gone for good; we might put ecological gloom-and-doom to rest and embrace a more positive attitude about our prospects on a humanized planet; technology, including risky, centralized, and industrial-scale systems, should be embraced as our destiny and even our salvation.”

Erle Ellis, an environmental scientist at the University of Maryland, has posted a fierce credo meant to help environmentalists prepare for the new order:

“Stop trying to save the planet. Nature is gone. You are living on a used planet. If this bothers you, get over it. We now live in the Anthropocene, a geological epoch in which Earth's atmosphere, lithosphere, and biosphere are shaped primarily by human forces.”

Wilson continues:

Like it or not, we remain a biological species in a biological world, wondrously well adapted to the peculiar conditions of the planet's former living environment, albeit tragically not this environment or the one we are creating. In body and soul, we are children of the Holocene, the epoch that created us, yet far from well adapted to its successor, the Anthropocene.

What passion drives the human juggernaut? It is manifested in the ordinary experience of our daily lives and in the unquestioned idioms of our language. Crist continues her analysis:

“Takeover (or assimilation) has proceeded by biotic cleansing and impoverishment: using up and poisoning the soil, making things killable, putting the fear of God into the animals such that they cower or flee in our presence; renaming fish "fisheries," animals "'livestock," trees "timber," rivers "freshwater," mountaintops "overburden," and seacoasts "beachfront," so as to legitimize conversion, extinction, and commodification “ventures.””

***

It has been my impression that those most uncaring and prone to be dismissive of the wildlands and the magnificent biodiversity these lands still shelter are quite often the same people who have had the least personal experience with either. I think it relevant to quote the great explorer-naturalist Alexander von Humboldt on this subject as true in his time as it is in ours: "The most dangerous worldview is the worldview of those who have not viewed the world.”

Tamanend had a different view of his world than Minuit. For Tamanend, Manhattan Island was an abundant cornucopia of friendly relations, to be stewarded, husbanded, and protected. For Minuit, it was a capital acquisition entered into the ledger of his company’s fortunes, towards which no more obligation was due than to regularly harvest, with native slave labor if possible, its generous bounty.

This past weekend the Dutch ruling coalition splintered and collapsed after proposing to limit the entrance of children of Ukrainian war refugees who are already in the Netherlands—to prevent those families from being reunited. The right wing felt that immigrants, especially the sick, elderly and young, dilute the “hard-earned” wealth of their nation. The left felt these policies were too cruel for compassionate people to support. Instead, the government toppled.

It was a pity, because it makes even less likely that the Lenapehokink will receive any kind of reparations for their dispossession and the cruel genocide and enslavement by Peter Minuit and his Dutch compatriots.

Or for that matter, that Lenape sovereignty will be recognized by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania any time soon.

What is even sadder is that we have thus far forsaken the only way out of our annihilation by climate change, eloquently set out by Wilson in Half Earth, electing instead to pursue chimeras of Anthropogenic machinations.

In the Braiding Sweetgrass chapter, “The Gift of Strawberries,” Robin Wall Kimmerer writes:

Something is broken when the food comes on a styrofoam tray wrapped in slippery plastic—a carcass of a being whose only chance at life was a cramped cage. That is not a gift of life. It's a theft. How in our modern world can we find our way to understand the Earth as a gift again? To make our relations with the world sacred again? I know we cannot all become hunter-gatherers. The living world could not bear our weight. But even in a market economy can we behave as if the living world were a gift?

***

Refusal to participate is a moral choice. Water is a gift for all not meant to be bought and sold. Don't buy it. When food has been wrenched from the earth-depleting the soil and poisoning our relatives in the name of higher yields don't buy it. In material fact, strawberries belong only to themselves. The exchange relationships we choose determine whether we share them as a common gift or sell them as a private commodity. A great deal rests on that choice. For the greater part of human history and in places in the world today common resources were the rule. But someone invented a different story—a social construct in which everything is a commodity to be bought and sold. The market economy story has spread like wildfire with uneven results for human well-being and devastation for the natural world. But it is just a story we have told ourselves. And we are free to tell another—to reclaim the old one.

Meanwhile, let’s end this war. Towns, villages, and cities in Ukraine are being bombed every day. Ecovillages and permaculture farms have organized something like an underground railroad to shelter families fleeing the cities, either on a long-term basis or temporarily, as people wait for the best moments to cross the border to a safer place or to return to their homes if that becomes possible. There are 70 sites in Ukraine and 500 around the region. As you read this, 24 Ukrainian ecovillages have given shelter to more than 2500 people (up to 500 children) and now host up to 1400 persons (around 200 children). We call our project “The Green Road.”

For most of the children refugees, this will be their first experience in ecovillage living. They will directly experience its wonders, skills, and safety. They may never want to go back. Those that do will carry the seeds within them of the better world they glimpsed through the eyes of a child.

Those wishing to make a tax-deductible gift can do so through Global Village Institute by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by directing donations to greenroad@thefarm.org.

There is more info on the Global Village Institute website at https://www.gvix.org/greenroad or read this recent article in Mother Jones. Thank you for your help.

The COVID-19 pandemic destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed climate change, a juggernaut threat to all life, humans included. We had a trial run at emergency problem-solving on a global scale with COVID — and we failed. 6.88 million people, and counting, have died. We ignored well-laid plans to isolate and contact trace early cases; overloaded our ICUs; parked morgue trucks on the streets; incinerated bodies until the smoke obscured our cities as much as the raging wildfires. The modern world took a masterclass in how abysmally, unbelievably, shockingly bad we could fail, despite our amazing science, vast wealth, and singular talents as a species.

Having failed so dramatically, so convincingly, with such breathtaking ineptitude, do we imagine we will now do better with climate? Having demonstrated such extreme disorientation in the face of a few simple strands of RNA, do we imagine we can call upon some magic power that will arrest all our planetary-ecosystem-destroying activities?

As the world emerges into pandemic recovery (maybe), there is growing recognition that we must learn to do better. We must chart a pathway to a new carbon economy that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backward — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience. We must lead by good examples; carrots, not sticks; ecovillages, not carbon indulgences. We must attract a broad swath of people to this work by honoring it, rewarding it, and making it fun. That is our challenge now.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

Thank you for reading The Great Change.