I am busy with international travel this week but this story is one of my favorites.

August 04, 2019

"A foray into genealogy prompts some observations about the Anthropocene."

Last week, an historic heat wave inflicted life-threatening temperatures on Europe and shattered all-time high temperature records in multiple countries. On Thursday, Paris registered a heat-stroking 108.7 °F, breaking its record of 104.7 °F set in 1947. England, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands all topped historic highs. Unable to cool themselves, French nuclear reactors dropped 6.6 GW from the grid just as air conditioning was cresting a new peak. In England, rail service out of hot cities to the cooler countryside had to be cancelled when steel tracks began to warp. And yet, the next day, Friday, the penultimate stage of the Tour de France was cancelled mid-race by sudden summer ice and hail which turned to slush, flooding roads and bringing a small landslide tumbling down onto the course.

Amidst this climate of chaos, I rented a bike and cycled the paths of Romney Marsh, in southeastern England, ghost-hunting.

Through a series of fortunate events, I discovered a couple of years ago that I am descended from Issachar Bates, the Shaker hymnist and explorer, and the founder of Pleasant Hill Shaker Village in Kentucky. This opened an interesting chapter in genealogy for me as I was then able to learn the time and place of my family’s arrival to North America.

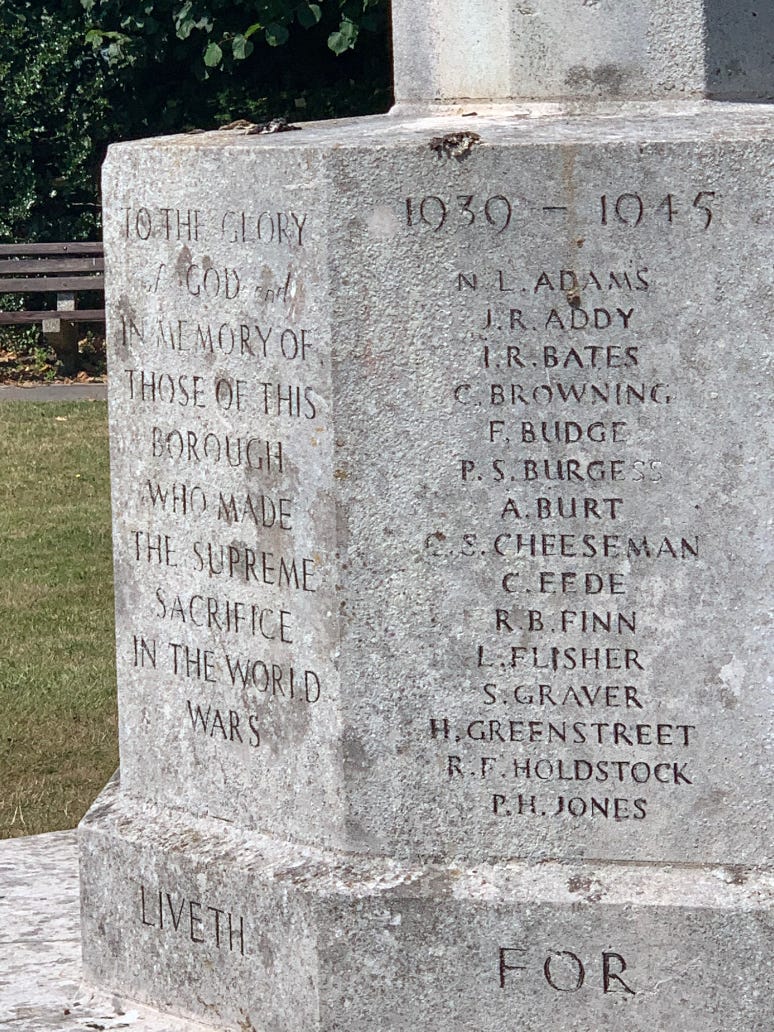

In 1623, my 8th great-uncle, 24-year-old John Isaac Bates, departing the small farming town of Lydd, Kent, in the indenture of Abraham Piersey, a wealthy slaver and plantation owner, boarded the ship Southampton, and arrived, in January 1624, to the Jamestown Colony. John grew for his master the first crop of tobacco to be exported to England and, after seven years of that kind of toil in Kent County, Virginia, became a free man. It is recorded that his oldest son, my 7th grand-uncle George Bates, met George Fox (1624-1691), founder of the Quaker movement, and became an early convert.

In 1635, at age 41, my 8th great-grandfather, Clement Bates, also of Lydd, who was 17 when the King James Version of the Bible was published, gave up his class position, sold his estate and possessions, packed his wife and five children, aged 2–14, and two indentured servants aboard the three-masted, square-rigged Elizabeth, and sailed for Plymouth Colony. Why this second Bates decided to leave a place where the Bates family had been born and died for more than 400 years is a complicated story, involving Popes and Kings, religious tribal feuds, apostates and evangelists, but suffice it to say he thought a better life would be found in the New World. Like his relative, George the Quaker, my 4th great-grandfather Issachar had a religious conversion when he met Mother Ann Lee, and became a Shaker, eventually founding a utopian pacifist communal society of 500 converts on 2000 acres in the Kentucky hill country.

When I first had a look at Lydd on Google Earth it was apparent to me that this was a spot of land not long for this Earth. It would, perhaps within the course of this century, dip beneath the waves and probably not re-emerge for a million years. I was likely wrong about that, as we shall see, but the idea was powerful enough that when I found myself with a week to spare between a book-signing event in Gloucestershire and a permaculture design course in Ireland, I decided to make a return pilgrimage.

I trained to Rye, rented an e-bike and scooted to a BnB caravan rental adjoining Rye Harbour Nature Reserve. Each day, I took the bike to the limit of its 50 km range as I roamed Romney Marsh, trying to get a sense of what it would be like for a family going back to at least James Bate in 1200 and possibly earlier. Neither Lydd nor Bate is listed in the Domesday Book written in 1086 (the “great survey” taken at the order of William the Conquerer following his Norman success at the Battle of Hastings). Hastings was one of my day trips, although I would have to say Battery Hill, a significant climb from Pett Level to the Napoleonic war cannon battery above Hastings, is appropriately named for the challenge it offers an e-bike. I was able to recharge in Hastings, thanks to the garage outlet of my gracious host, Craig Sams, founder of Green & Black and CarbonGold.

In the Middle Ages, upward mobility was nonexistent. Hence, it is fair to assume, not having been listed in the Domesday Book, that my family was not among the landed gentry. Still, my 19th great-grandfather, born in 1270, is listed as being a “Senior Master” or one of the King’s Court judges, during the reigns of Edward I and Edward II. In those times “s” was added to a surname to signify the son of a patriarch, so Bate became Bates with the judge’s son, also a judge, and thereafter.

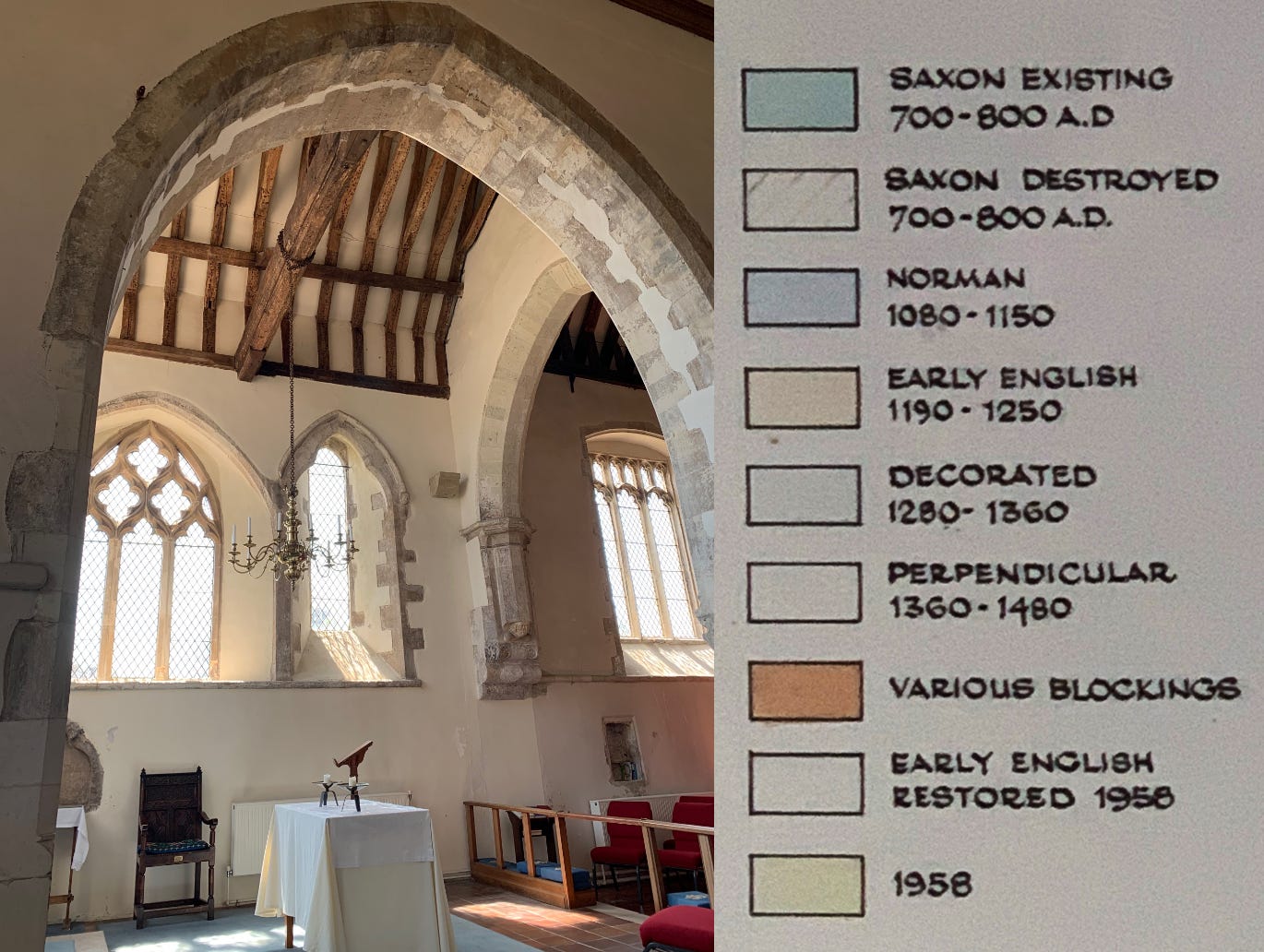

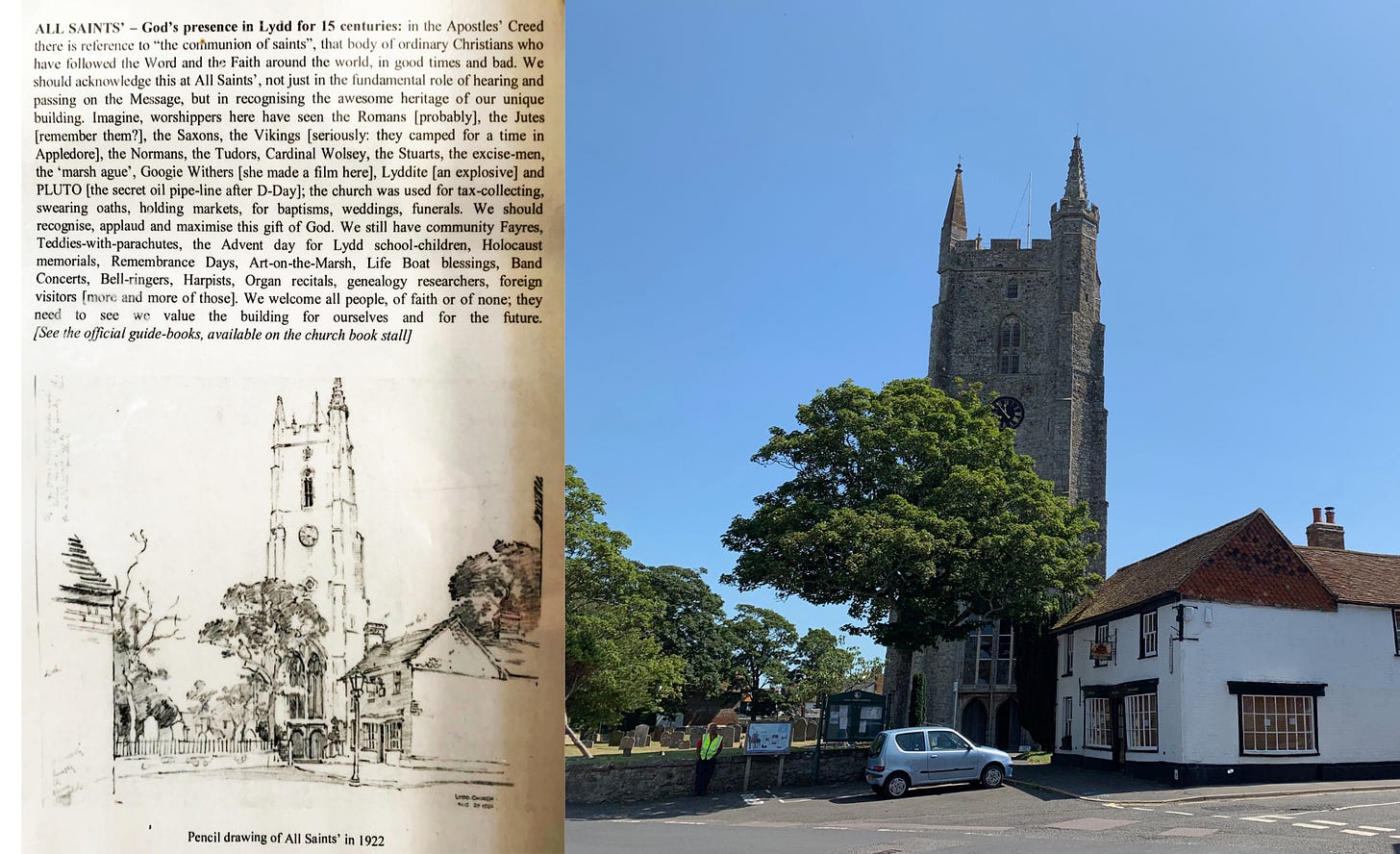

Rather than progress through the centuries of John begat Henry who begat Albert, or describe that lovely old Saxon cathedral in Lydd, I would rather pause the bicycle here beside the track through the marsh and assay the lay of the land. One of the first clues that I could be wrong about Lydd going beneath the waves as Greenland melts is an observation that it has been moving in the opposite direction for nearly 800 years.

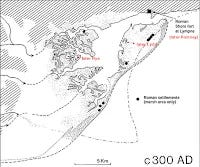

Prior to the 13th century, Lydd had been a part of the Cinque Ports, a confederation centered around the city of Romney, where the river Rother flowed out of the Rother Valley in Sussex, past the large Isle of Oxney, home to the city of Wittersham, past the towns of Tenterdem and Appledore and out to the Dover Channel through the grand harbor at Romney. On an island across the bay from prosperous Romney was my little ancestral town of Lydd.

As the closest point across open water from Calais, this was where the Romans had landed, and then the Normans, and where Napolean and Hitler had planned to arrive. It was within sight of the beach at Lydd that the tall ship parade of the Spanish Armada had passed in 1588. However, by that time Romney had ceased to exist, Lydd had ceased to be an island known for its pirates and smugglers, and what existed in their place was a broad expanse of lowlands with broadscale wheat farms and sheep herders. The Roman harbor was gone, the Norman landing beaches were gone, and the world had changed for the Cinque Ports.

The unexpected change had come on a single day in 1287. A great storm blew out of the Atlantic and struck Romney, first with destructive waves that sank the great trading fleet at anchor and uprooted the cobblestone streets, and then by a great upheaval of stone pebbles from the sea floor. Known locally as “shingle,” these round beach pebbles are typical of the coastline in this part of the world, and when I went swimming with Craig Sams near the Hastings pier, on the hottest day ever recorded in England, we wore rubber sandals to protect our feet.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great Change to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.