Seaweed Biochar Airplanes

What does the Doolittle Raid on Japan have in common with the Battle of Britain? — Aviation fuel.

James Harold Doolittle was born into a rocky river camp near Nome in 1896. His father, Frank, a carpenter-woodworker, had dragged the family from California to the frozen frontier chasing the shiny dust shaken from sieves and dreams of a quick fortune.

Through howling winters and black fly-biting summers, “Dusty” Doolittle grew up with his American father’s fearless recklessness and his German mother’s iron will. When mom left Frank to go back to California, Dusty boxed for nickels, hawked newspapers, and tinkered with engines. He was seven when Orville Wright defied gravity, sitting in front of a 12 HP, 1025 rpm, in-line four at Kitty Hawk.

At 15, while working as a janitor, “Jimmy” as he was then coming to be known, snuck into classes at U.C. Berkeley. At 21, he enlisted as a flying cadet in the Army Signal Corps Reserve. Training at Rockwell Field, he survived stalls and spins, earning his wings in 1918. After the war, he was a first lieutenant in the Air Service and a test pilot at McCook Field, where he pioneered instrument flying—no horizon, just gauges and guts. In 1922, strapped to a de Havilland DH-4, he executed the first barrel roll outside a loop, defying then-known physics to pull negative-G’s in a canvas-covered biplane.

To make that negative-G barrel roll, he first initiated a helical roll, in which the aircraft follows a looping path, experiencing sustained negative G-forces, meaning the aircraft pulls forward and downward while rolling, keeping the pilot “outside” the loop’s curve. He pulled back slightly on the stick to raise the nose, then transitioned to forward stick pressure (pushing the nose down) while applying continuous aileron input to roll the aircraft inverted, creating centrifugally negative G (-1 to -3G) where loose objects float toward the canopy, blood rushes to the head (no pressure suits in 1922) and structural stress on the aircraft spikes (the DH-4 had spruce spars and ribs with fabric covering, guyed by steel wires). Doolittle maintained forward pressure on the stick throughout the roll to follow an upward-concave circular path (opposite a standard positive-G barrel), rolling at a steady rate (often 1-2 seconds per 360°) while using rudder for coordination to prevent slipping or skidding, then, after one or more rotations, eased off forward pressure, pulling back gently to level the nose, and neutralized controls to exit, monitoring airspeed to avoid over-speeding or stalling.

Jimmy earned a doctorate in aeronautics from MIT in 1925, becoming the first aviator-physicist. Racing became his next passion: Schneider Trophy, Thompson Cup, Bendix—setting transcontinental race records despite permanent scars from crashes he walked away from.

Shell Oil recruited him in 1930 as its aviation manager. Ever the tinker, he took on the challenge of fuel knock. He persuaded Shell to build refineries to make 100-octane “avgas.” In 1934, the U.S. Army tested it and the first contracts repaid Shell for Doolittle’s refineries and then some. By 1940, RAF Spitfires were winning turbocharged dogfights over Britain.

Recalled as a major, then bumped up to lieutenant colonel, Doolittle pitched a mad raid on Tokyo to the brass. With a handpicked suicide group to fly “Special Aviation Project No. 1,” Doolittle launched 16 overweighted B-25 Mitchells from USS Hornet—his own leading the way into the wind from a pitching deck, the shortest, most unthinkable and untested launch roll in history. On April 18, 1942, 650 miles from the carrier, their bombs rained down on a shocked Japan. Doolittle’s own payload struck a schoolyard by error. In China, out of fuel, his and the other crew’s aircraft crash-landed in rice paddies.

Commanding the Twelfth Air Force in Africa and then the Eighth Air Force in England from pre-D-Day up to the liberation of Berlin, General Doolittle—he was by then called “Uncle Jimmy” by his crews—transformed the Army Air Corps into a co-equal military branch. Postwar, he forced the Air Force into jets. As a reserve lieutenant general, he advised on missiles, space and the ICBM Triad while sometimes sneaking away to glider soar over the Sierras. Perhaps he was thinking about what potential Einstein, Pauling, or daring young Doolittle might have died in that schoolyard in 1942.

Uncle Jimmy’s Legacy

Global aviation has committed to net-zero greenhouse emissions by 2050. Some 43 airlines have set corporate goals and timetables. They recognize that the warming trend is not their friend. It is a bad look for business. They know they currently contribute 2.5 percent of atmospheric carbon pollution—and rather than shouldering the blame or facing government restriction, they are trying to get out front with “sustainable aviation fuels” (SAF).

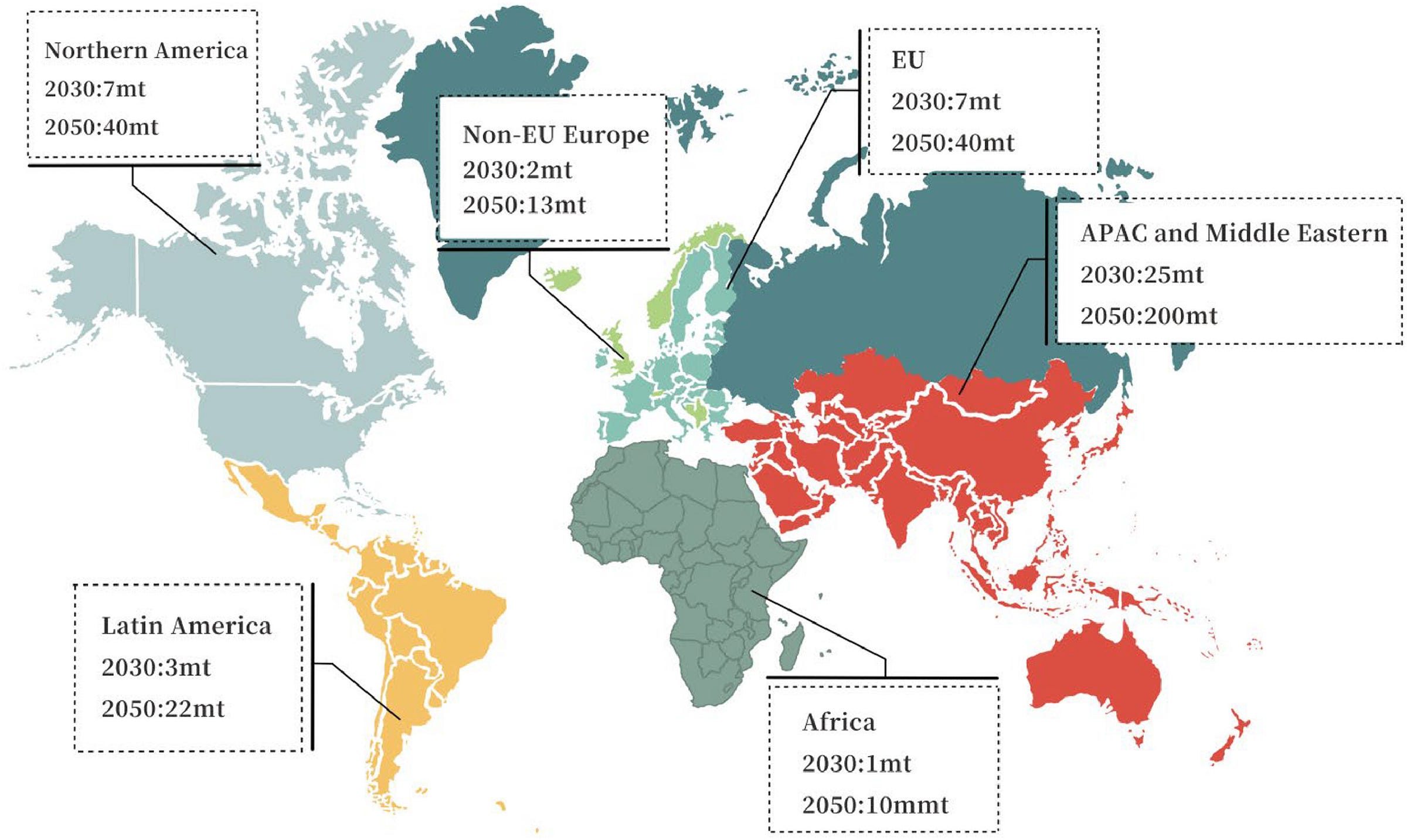

Doolittle pushed Shell Oil to invest in large‑scale production of 100‑octane fuel at a time when no aircraft required it. Now almost all do. Derived from fossil fuels, avgas consists of hundreds of hydrocarbons (primarily C8-C16 alkanes with long-chain polymers). To produce it, refineries perform multistage distillation. Avgas comprises various blends of kerosene, gasoline, and ethanol, along with additives. If Doolittle were alive today (he died in 1993), he might well be working on the SAF problem. It is estimated that by 2050, global annual SAF demand will reach 26 million tons (32.5 billion liters). It is presently doubling production annually, with China the growth leader. SAF now costs about $8.65 per gallon, compared with $2.80 for conventional jet fuel.