The Texcoco Marvel

How Aztec engineers tamed an environmental nightmare gives a lesson for today

In August, 2022, I described here on The Great Change how we had attempted to recreate an ancient indigenous farming method in the highlands of middle Tennessee.

This week I donned my tall boots and waded back into our constructed wetland to restore and rebuild the chinampas. Rob Wheeler, for more than 20 years the Global Ecovillage Network representative to the UN Headquarters in New York, brought along loppers, machete and a portable saber saw to assist me. During my nearly three years pandemic absence, the wetlands had taken on a life of their own and become a swampy thicket of fallen branches, bent-over bamboo, and nettles. One could be forgiven for not seeing beneath all that to what it will eventually become—the most productive food system, on a calorie per square foot basis, ever devised by humans.

Among the engineering wonders deconstructed by the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th and 17th centuries were the vast systems of chinampas that sustained a dense metropolitan population in the high central valley of México. Their aquatic earthworks consisted of alternating narrow islands and canals, initially formed by willow fences and composted fill from the kitchen wastes, lake mud, rubbish and sewage of the lakeside villages, planted with fruit and nut trees to line and hold the banks and gardens of corn, beans and vegetables. Freshwater fish were trapped by fences in the canals where they ate mosquito larvae and grew fat on falling fruit until they could be netted and brought to market.

A 2014 study of the chinampas in the 70-square-mile Lake Chalco-Xochimilco found they were built between the mid-15th and early 16th centuries at the peak of the Aztec Triple Alliance. In a ten-square mile study area, 23,094 relic beds and 400 mounds were digitized for mapping. The long, narrow beds averaged 3.75 meters wide and had an average length of 49.4 meters, with a land-to-water ratio of 1.07:1. In addition, there were many small lakeside homes and villages, large wharves comprised of multiple mounds and platforms, open pools, and wide canals.

According to the researchers, chinampas allowed frost and flood protection, nutrient recovery, and irrigation by splash or scoop techniques from canoe-bound farmers during droughts (the standard tool was a lacrosse-stick-like ladle called a zoquimatl). Normal capillarity flows from the lake through the island eliminated the need for irrigation in dry cycles. Large amounts of algae (known as tecuitlatl) were collected from the surface of the Lake and used to make high-protein bread and cheese-type foods. This algae is still grown in Mexico for fertilizer.

Last month I described how the new president of México should learn from that history and re-establish these systems by restoring the indigenous ecology of the high valleys. I used images drawn by Dall-E to reimagine that near-future steam-punk utopia.

Chinampas are a permaculture technique I would always teach in my two-week permaculture design courses, and I thought that the images drawn from old Mexican textbooks that I put up in PowerPoints were pretty good. But then, last week, Tomas Pueyo published his own history of that ecosystem design to his blog, Uncharted Territories, and I was humbled. Here is one image, recreated with A.I., of how the Aztec Capitol may have looked to a chimay at the arrival of Hernan Cortés.

In my post last month, I wrote:

The Conquistadors could not fathom the island city of Tenochtitlan when, on November, 8, 1519, they crossed the Ixtapalapa causeway over Lake Texcoco and beheld the spectacle of its glimmering central pyramid, broad white boulevards, and flowered verges. It was the most beautiful city any of them had ever beheld. Cortés and his men marched across the causeway until they were met by the Aztec Emperor, Moctezuma II, who greeted them, descending his royal litter to offer gifts. Moctezuma was immediately taken prisoner and ransomed for gold and silver. Once the ransom was paid, he was executed.

Six months later the Aztecs rose up and threw out Cortés, but it was too late. While the Spanish army spent 1520 exiled to Tlaxcala, General Smallpox ravaged and decimated the city, reducing its mighty army to bleeding pustules.

The system of chinampas was impressive but perhaps even more impressive, and described by Pueyo, was an engineering feat of the 16th century Aztecs that rivals anything in either the ancient or modern world. The high valley of Central Mexico is surrounded by volcanoes and mountains. The water from all these mountains flows to the center, where it can’t escape because ancient lava flows blocked the exits. So instead, the water accumulated in vast lakes, which lay down rich sediments of volcanic mineral soils. Whether for defensive reasons or because aquaculture was a pillar of their food supply, the Aztec capitol was built on islands in the largest lake, but there was a public health problem.

The inland sea was salty. It was toxic to irrigation and freshwater fish. It must have been a nightmare breeding ground for mosquitoes and smelly algal blooms. So what did the Aztecs do? Pueyo answers:

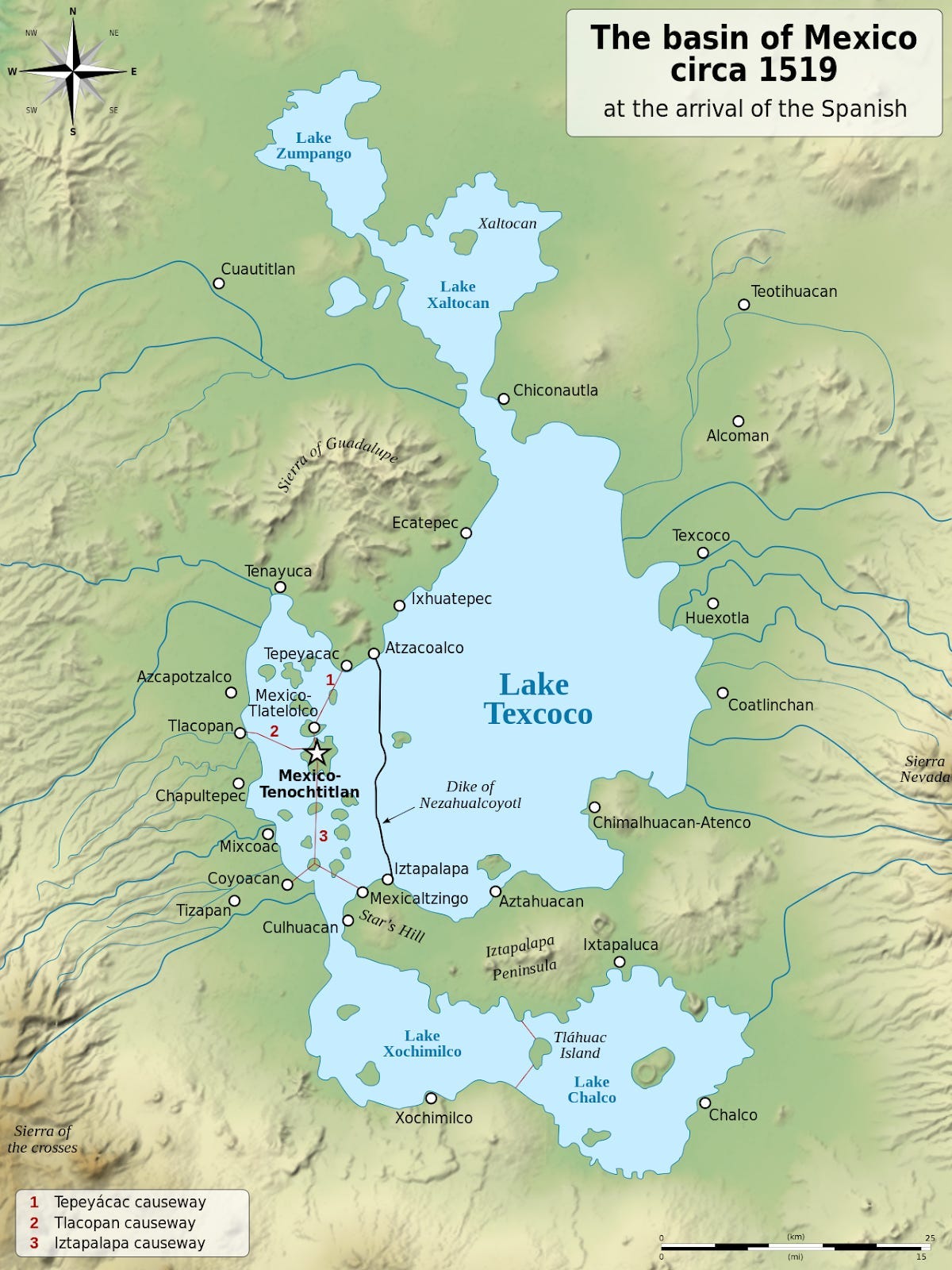

The Aztecs built a levee (“Dike of Nezahualcoyotl” on the map) to split the lake in half. The lower altitude part would accumulate all the salty water, while the upper part would accumulate the fresher water from the mountains. And which of these halves is at a higher altitude? The one where Tenochtitlan lies. This dike meant the city was surrounded by freshwater instead of saltwater, which allowed easy irrigation on the islands and surroundings, and hence agriculture.

Moreover, they closed the cycle of pollution from their city by turning all their sewage and kitchen wastes to compost and then building chinampas that extended out into the freshwater lake. Fruit trees planted on the island perimeters sent down roots that replaced the decaying wicker bulwarks that separated the new land from the lake, holding the islands in place permanently.

But what of that dike? That is what drew my attention when I read the piece. Look at the map. That bridge that passes from North to South, bisecting the lake, is 25 miles long. The Aztecs did not have cranes and concrete. They had boats and baskets. And yet they made a causeway that is nearly four times longer than the Seven Mile Bridge connecting Key West to Florida, which is actually 6.79 miles long. Any of the three causeways on the map that connect the island city to the mainland are more than twice as long as Florida’s second longest — the Long Key Bridge, at 2.3 miles.

I am reminded of another engineering marvel I visited a few years ago in Dujiangyan City, Sichuan, China (都江堰). Originally constructed around 256 BC by King Zhaoxiang (秦昭襄王) of Qin, it is still in use today. During the Warring States period over 2,250 years ago, people who lived in the area of the Min River were plagued by annual flooding. The royal hydrologist Li Bing investigated the problem and discovered that the river was swelled by fast-flowing spring melt-water from the local mountains that burst the banks when it reached the slow-moving and heavily silted stretch below. One solution would have been to build a dam, but fortunately the King lacked an Army Corps Engineers to advise him. Instead all he had were Taoist priests. They said, do not fight the water, bend it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great Change to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.