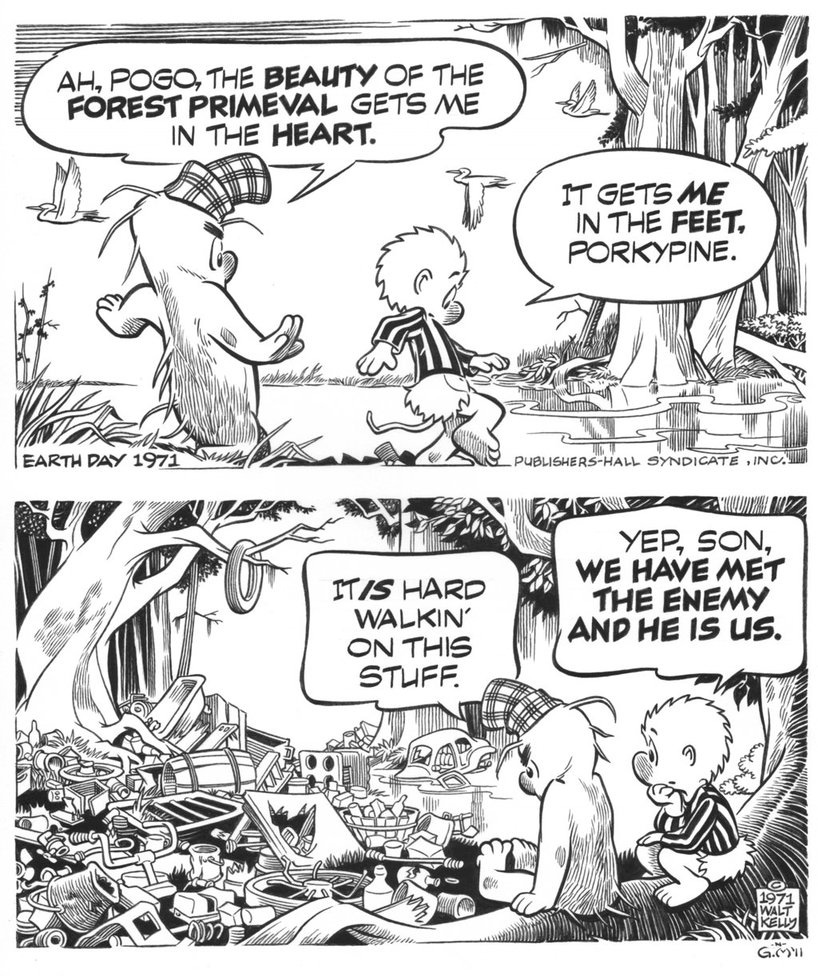

It is getting less uncommon that the things I choose to write are overtaken by events, almost as soon as they are published. Two posts ago I told y’all that erratic weather patterns were confounding farmers all over the the world. Last week I described how Central Europe had been beset by the Boris supercell that came from a seemingly fluke loop in the polar vortex. “Seemingly fluke” is how magic, sorcery, or divine intervention are often attributed when natural events like eclipses and earthquakes strike. On closer examination, we can usually ascribe an author, and where weather weirding is concerned, that’s us.

The fluke loop in the polar vortex that added 10 billion euros to the GDP of Central Europe in four days was a wobble in the jet stream created by the temperature differential between the equator and the North Pole, generated by global heating, which in turn, was caused by burning 100 million years of stored sunlight in less than two centuries. We are on track to burn that much in the next 10 years as we burned in all that previous time.

When Svante Arrhenius saw what was happening in 1896, he thought it would take thousands of years for the pace of change to increase this much and predicted that as temperatures rose, people would "live under a warmer sky and in a less harsh environment than we were granted.” Arrhenius thought that global warming would allow people to move into colder regions and produce more food for the growing population. He was not entirely wrong in that, but there are limits.

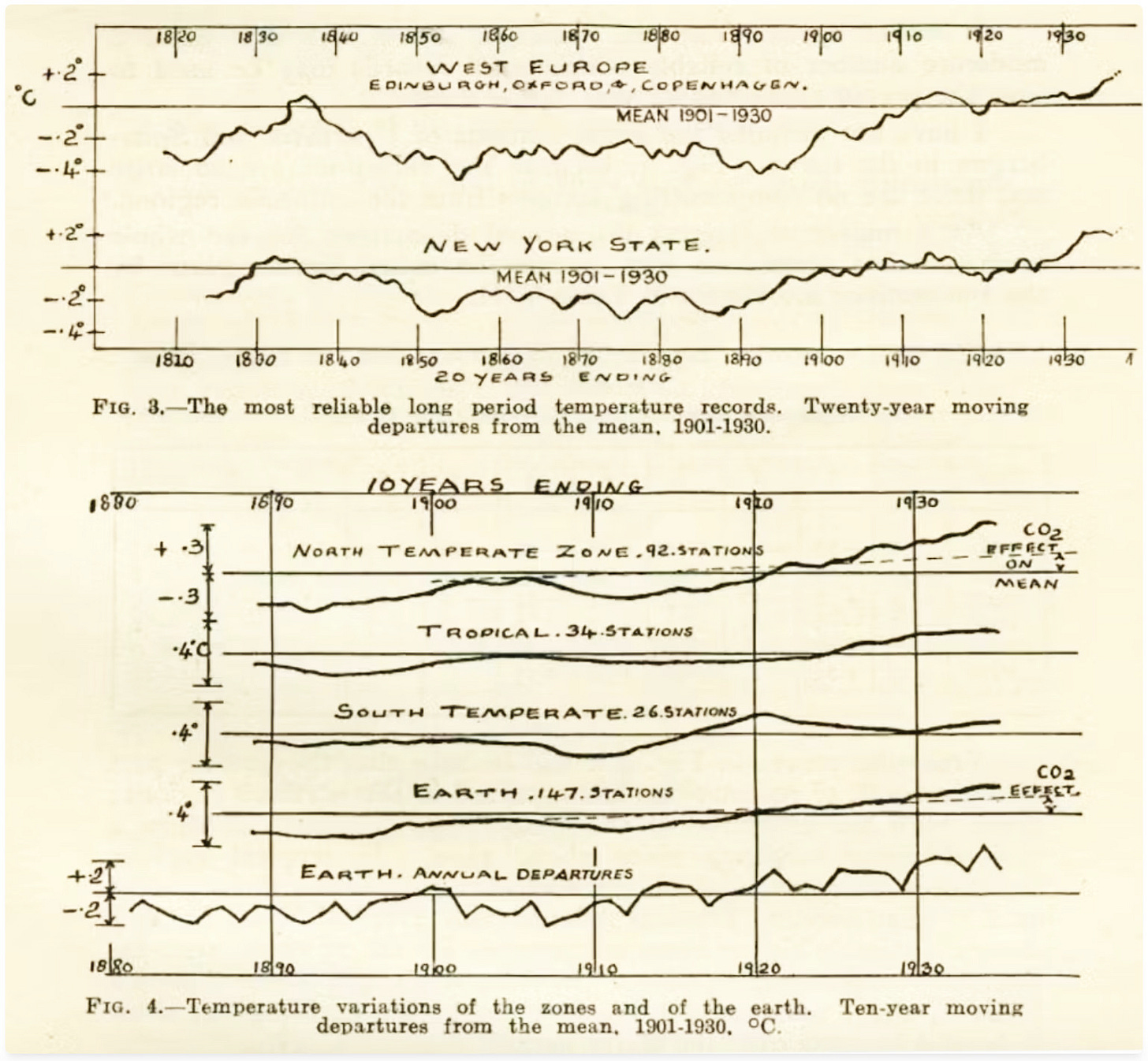

Like Arrhenius, amateur climatologist Guy Callendar in 1938 also had a positive outlook, predicting increased crop production in the northern hemisphere and that heating would “forestall the return of the deadly glaciers.”

His theory became widely known as “the Callendar Effect.” Today, it’s known as global warming. Callendar defended his theory until his death in 1964, increasingly bewildered that the science met such resistance from those who did not understand it.

Arrhenius and Callendar stood on the shoulders of Eunice Newton Foote who first measured the greenhouse effect—specifically the absorption of heat by carbon dioxide and water vapor when exposed to sunlight—in 1856, and John Tyndall, whose work was on the infrared absorption by atmospheric gases, in 1859. These 19th-century leaders assumed that most of the pollution created by fossil fuels would be absorbed by the ocean. Living in the era of unlimited whaling, they might have been shocked to learn what was shown by Roger Revelle and Hans Suess in 1957—that the ocean had only a limited ability to buffer human impact. Our deleterious impact was shown more conclusively by Charles Keeling’s air samplings commencing March 29, 1958, when the atmospheric CO2 concentration was 313 ppm (it had grown to 422.99 ppm by August 2024).

As I write this, the United States is still experiencing the effects of its worst hurricane season in history. In late September, Helene sprang up suddenly, underwent rapid intensification in the warm ocean waters foreseen by Revelle and Suess, and exploded from tropical depression to Category Four in about 48 hours, picking up enough speed and momentum to travel 1000 miles inland after making landfall. At this writing we are watching another tropical depression form in almost the same location, possibly taking a similar trajectory (or not, it is too soon to say). This is like watching a prizefighter land a blow that staggers his opponent, and then following with the exact same punch. One-two. Boom.

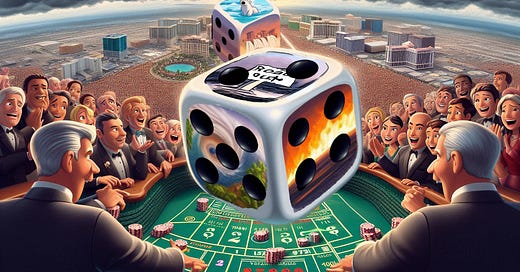

A better metaphor put forward by a great departed climate scientist was gambling with dice. Stanford biologist Stephen Schneider was one of the first scientists to devise an approach for detecting signs of climate change, distinguishing unnatural from natural variations. If asked to explain Helene et sequelae, he would likely put it this way: the Gulf of Mexico's abnormal water temperature of around 85°F is like adding extra weight to one side of a die at the craps table in Las Vegas. Provide more energy for a tropical cyclone to strengthen quickly, and you increase the odds of a major hurricane. The warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, which is like adding spots to the "heavy rainfall" side of the die. This loads the dice for your hurricane to produce extreme precipitation and flooding as it moves inland.

Climate change has already caused sea levels to rise, which is like tilting the table on which we're rolling the "storm surge" faces of the dice. Climate change can also cause hurricanes to move more slowly and meander once they make land, dumping massive rainfall. This adds weight to the "inland flooding" sides of the dice. Results of prolonged, heavy rainfall in affected areas are dam failures, mudslides, and extreme, unprecedented flood damage. Moreover, a rapidly warming climate is expanding the regions where hurricanes can form or maintain their strength after forming, even after landfall. This is like enlarging the number of casinos where dice are rolled, and the number of craps tables in each. Forget Miami. Think Asheville, North Carolina.

Schneider, true to his role as an IPCC lead author, would always hasten to add that we can't attribute any single event solely to climate change. His point was that the dice are increasingly loaded by warmer oceans, increased atmospheric moisture, rising sea levels, slower storm movement, and expanded risk zones, and that increases the probability of destructive outcomes. Cumulatively, they spell universal disaster. Given enough time, nowhere is safe.

The 19th-century discoverers of the greenhouse effect were not as concerned about all these effects because they did not fully appreciate their speed of onset. While Malthus discerned the relationship between food supply and population growth, he was less aware—arriving on the scene before the Industrial Revolution—of human wastes affecting the environment. Resource scarcity was the doomerist concern through most of the 19th and 20th centuries, not pollution.

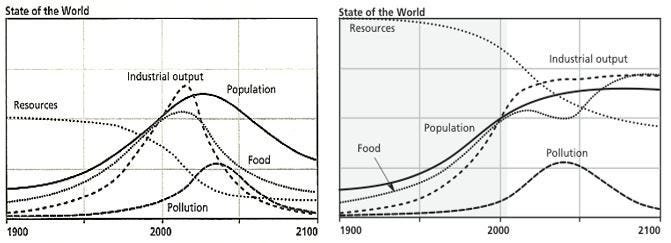

Eventually the concept of “carrying capacity” emerged from the work of Aldo Leopold and others. Biologist Eugene Odum was the first to theorize carrying capacity more comprehensively in his 1953 book Fundamentals of Ecology. He formulated it mathematically and denoted it as K in population growth equations. Paul Ehrlich and John Holden’s 1970 equation I=PAT (Impact = Population x Affluence x Technology) explicitly added pollution and other environmental impacts, not just food supply, to human limits, and that fed into Dennis and Donnela Meadows’ World3 computer model for the Limits to Growth report in 1972. Finally industrial waste, including greenhouse gases from fossil fuels, had become one of the five central variables, alongside population, food production, industrialization, and consumption of nonrenewable resources.

Ehrlich later said,

Even in 1968, I discussed how human activities, including pollution, could change the climate. I noted that putting "crap into the atmosphere" would alter climate patterns, though the specific outcomes (warming vs. cooling) were still debated at that time.

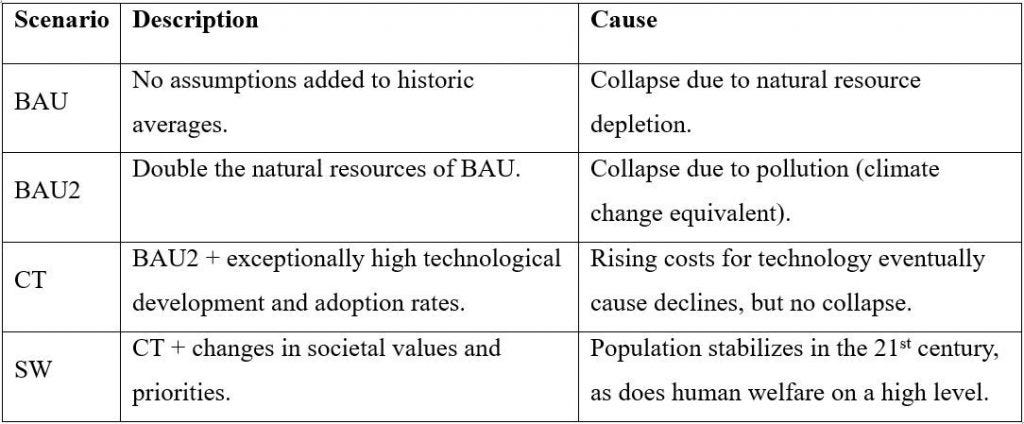

In the World3 "business as usual" (BAU) scenario, rising pollution contributed to overall system collapse. In the BAU2 scenario (with double the resources), pollution became the primary cause of collapse, as abundant resources led inevitably to untenable pollution. In other words, the better we did at our old model of civilization, the worse things got for us.

All ecology is circular. Human habitat patterns prior to the Anthropocene had been mostly linear. There was a phase shift awaiting, whether by choice or by force.

Either we will make that shift to circularity, with a rapid transition intensification, or we will perish from our own social and epigenetic inertia. The future is not yet written, despite the weirdness we are experiencing. Gaya Herrington, director of Sustainability Services for KPMG and a Club of Rome advisor, in 2021 advised the Club:

The close alignment to empirical data and the fact that the scenarios have not diverged much yet, together form a call to action. Hidden behind a seemingly ambiguous outcome of two best-fit scenarios that marginally align closer than the other two, hails the message that it’s not yet too late for humankind to change course and alter the trajectory of future data points. We have another choice. Although SW [“stabilized world”] tracks least closely, a deliberate trajectory change is still possible. That window of opportunity is closing fast.

The one-degree change in global temperature before 2020 brought a 20,000x increase in the frequency of extreme weather. Given the rapidity of ever-accelerating change that has already turned the corner and is progressing almost straight up on its X-axis, frequency of extreme weather may already have doubled again between 2020 and 2024. What “extreme” will mean by 2030 is unknowable.

I began this unexpected series with Hurricane Francine, but I could have started it a week earlier with Cat 5 Typhoon Yagi (heaviest rainfall in Japan since 1929; 50,000 displaced in the Philippines; over 1 million evacuated in China; 291 deaths in Vietnam; continuing damage to Burma, India and Bangladesh) or the flooding in the Sahel that killed 465 people, displaced 290,000 and affected more than 4.4 million in six countries. It was a busy September.

What goes around comes around. A meandering river of air turns into a waterfall in the South Pacific. Then Central Europe. Then the US Southeast. As Pete Seeger sang, "When will we ever learn?"

References:

Bradshaw, C.J., Ehrlich, P.R., Beattie, A., Ceballos, G., Crist, E., Diamond, J., Dirzo, R., Ehrlich, A.H., Harte, J., Harte, M.E. and Pyke, G., 2021. Underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 1, p.615419.

Bradshaw, C.J., Ehrlich, P.R., Beattie, A., Ceballos, G., Crist, E., Diamond, J., Dirzo, R., Ehrlich, A.H., Harte, J., Harte, M.E. and Pyke, G.H., 2021. Response commentary: underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 2, p.700869.

Dirzo, R., Ceballos, G. and Ehrlich, P.R., 2022. Circling the drain: The extinction crisis and the future of humanity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 377(1857), p.20210378.

Ehrlich, P.R. and Ehrlich, A.H., 2022. Returning to “normal”? Evolutionary roots of the human prospect. BioScience, 72(8), pp.778-788.

Forrester, J. W. (1971). World Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Wright-Allen Press.

Forrester, J. W. (1975). Collected Papers. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications.

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., & Randers, J. (2004). The limits to growth: The 30-year update. White River Junction VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co.

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J. & Behrens, W. W. (1972). The limits to growth: A report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. New York: Universe Books

Odum, E.P., 1971. Fundamentals of ecology. Printing Company Ltd.

Rice, M.E., 2021. Paul R. Ehrlich: Of Bombs and Butterflies. American Entomologist, 67(4), pp.16-22.

Meanwhile, let’s end these wars. We support peace in the West Bank and Gaza and the efforts to bring an immediate cessation to the war. Global Village Institute’s Peace Thru Permaculture initiative has sponsored the Green Kibbutz network in Israel and the Marda Permaculture Farm in the West Bank for over 30 years and will continue to do so, with your assistance. We aid Ukrainian families seeking refuge in ecovillages and permaculture farms along the Green Road and work to heal collective trauma everywhere through the Pocket Project. You can read all about it on the Global Village Institute website (GVIx.org). Thank you for your support.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger, Substack and Medium subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions can be made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration.

當人類被關在籠内,地球持續美好,所以,給我們的教訓是:

人類毫不重要,空氣,土壤,天空和流水没有你們依然美好。

所以當你們走出籠子的時候,請記得你們是地球的客人,不是主人。

When humans are locked in a cage, the earth continues to be beautiful. Therefore, the lesson for us is: Human beings are not important. The air, soil, sky and water are still beautiful without you. So, when you step out of the cage, please remember that you are guests of the Earth, not its hosts.

We have a complete solution. We can restore whales to the ocean and bison to the plains. We can recover all the great old-growth forests. We possess the knowledge and tools to rebuild savannah and wetland ecosystems. It is not too late. All of these great works are recoverable. We can have a human population sized to harmonize, not destabilize. We can have an atmosphere that heats and cools just the right amount, is easy on our lungs and sweet to our nostrils with the scent of ten thousand flowers. All of that beckons. All of that is within reach.